Notice (8): Trying to access array offset on value of type null [APP/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp, line 54]Code Context $user = $this->Session->read('Auth.User');

//find the group of logged user

$groupId = $user['Group']['id'];

$viewFile = '/var/www/html/newbusinessage.com/app/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp'

$dataForView = array(

'magazineArticle' => array(

'MagazineArticle' => array(

'id' => '613',

'magazine_issue_id' => '472',

'magazine_category_id' => '0',

'title' => 'Partners In Economic Growth',

'image' => null,

'short_content' => null,

'content' => '<div>

<img alt="Cover Story" src="/userfiles/images/CS%20(Copy).jpg" style="width: 550px; height: 540px; margin-left: 10px; margin-right: 10px;" /></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 16px;">Multi-stakeholder Approach is the recent buzzword in development literature. How can Nepal use this approach? <strong>Achyut Wagle </strong>analyses the challenges and opportunities.</span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

When we say 'engaging development actors' we are talking about hierarchical operational levels like local, district, sub-regional, regional, national, international and global, where each of these levels form a complex matrix of actual actors primarily from five sectors -- the public or government, private or business, civil society, actual beneficiaries or common people and, development partners (donors). </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The economic growth is only possible through multidimensional interactions among these different groups of actors that are defined by the recent development literature as multi-stakeholder approach of development. The scope and limitation of the roles of each of these and conflicts and/or complementarities of the interests of these actors, singly or jointly, determines both the scale and the speed of the economic growth of any country, including Nepal. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

However, there is a problem in the definitional level, that is, whether all players in Nepal could be covered by these five categories of development actors mentioned above. Take for example Nepal's political parties who on their own right want to be the development actors, whereas their role and influence in development domain should either come through the public sector (for those who win the election and form the government) or only as the common people or the beneficiary (until they win the next election). The face of the civil society, if it has any, is not different from that of the political parties. In international practice, donors do not figure out with separate identities, who in Nepal's case appear even more quintessential actors. These distortions have serious implications both in engaging the development actors in their due roles and also attaining the ultimate results of our development endeavours. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 16px;"><strong>Actors</strong></span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>1. The Government</strong></span></div>

<div>

It is obvious that we need government for governance, hopefully a good governance. Although Nepal is not an exception among the least developed nations that face the crisis of governance, but one additional dimension in our case is we persistently face deficiency of democracy, perhaps more acutely at present. Nepal's politics during the last six decades of modern history has invariably been dominated by the dictatorial forces of some form that didn't believe in pluralistic, competitive democracy. This has been the main source of crisis of governance in general, manifested in the form of rule of force than rule of law, poor growth of institutions and their effectiveness, haphazardly conceived and weakly implemented policies, misuse of the state power by the powerfuls, strong nexus between the crime and law enforcement, utter lack of transparency and rampant corruption in public expenditure, rise of business syndicates and, worst of all, pervasive and persistent impunity. And, the list can on, and on.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

We don't have elected local governments at the local and district levels for last one decade, for no tangible reason for this vacuum, except for the height of irresponsibility and imperviousness of the political actors of the country. It should have in fact been the first priority of all particularly after the signing of Comprehensive Peace Treaty seven years ago; as the local governments would have been the best channels to deliver the much touted about peace dividend, many of the economic rights and delivery of the public services at the grassroots. Above all, it would have provided the people at the grassroots with direct access to the state mechanism. One can only imagine at this point, how many of new generation of leaders this process would have produced and how much would it have facilitated the process of proposed federalization of Nepal.</div>

<div>

Nepal never created democratic government institutions at sub-regional or regional levels. We have bureaucratic arrangements like regional administrators who virtually have no role in economic planning and development except for that of official messengers.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<img alt="The Engagement Matrix" src="/userfiles/images/CS2%20(Copy).jpg" style="width: 550px; height: 307px; margin-left: 10px; margin-right: 10px;" /></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

At the national level, we have Himalayan scale of policy confusions at development governance. We still have National Planning Commission (NPC) located inside the high walls of Sigha Durbar, that mercifully distributes development to the people of far and wide corners of Nepal. We still believe that the people who live in NPC as if have divine senses to understand the exact development needs of the people living at Tinker and Olangchung Gola and ability to address them from here. The duplication of the roles between the finance ministry and NPC, the constant squabbles and ego-clashes of the mandarins in them is staple national drama. The independence of central bank has always been a mirage, as we saw ten governors in Nepal Rastra Bank in as many years. We never had and, nor will have the possibility of implementing an independent monetary policy of our own in foreseeable future due to 'pegging' of Nepali currency with the Indian Rupee.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

At the international level, Nepal is gradually losing its credibility as a viable economy. We have not been able to organize the Nepal Development Forum, to interact with our international development partners, for the last one decade. Our ability to communicate about our needs with them and prioritize development areas to streamline their support has substantially reduced. The torch-bearers of our economic diplomacy are the political nominees typified, for example, by the recently sacked Nepali ambassador to Qatar. We may talk about FDI, but it has even stopped trickling in. We have also failed to introduce a functional mechanism to make sure that all official foreign assistance is spent through our budget, despite the fact that many of the donors are in favour of such a system.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>2. The Private Sector</strong></span></div>

<div>

The post-1990 marked an era that tried to put the private sector in the driving seat of economic growth. The policies of liberalization, privatization and legal as well as institutional reforms initiated by the first elected government after reinstatement of democracy brought about substantial positive changes, the impact of which has withstood violent conflict of a decade. Private airlines, large private sector banks, private hospitals, multiple universities, private investment in communication, information technology and hydropower, and private participation in building infrastructures like roads and irrigation facilities are some of the exemplary outcomes of these policies.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

But this encouraging trend was abruptly truncated by the armed conflict waged by the Maoists and, after seven long years after cessation of hostilities too, there is no certain sign of putting the policy of private-sector-led growth back on track. The political mayhem we are witnessing even after the second Constituent Assembly elections last month is even more disgusting to say the least.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Needless to say, three preconditions for private sector actors to come forward to contribute to economic growth are: ensured private property rights, an appropriate business climate that encourages investment and a predictable policy regime that provides a reasonable time horizon for conceptualizing, executing, operating and if needed closing of the businesses without being unnecessarily anxious about the safety of, as well as, return from the investment.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

But, the greatest challenge to all of these aspects not only comes at the operational level but at the level of the very philosophy of the strongest of the political forces of Nepal. Confiscation of the private property, politically patronized trade unions disturbing the industrial atmosphere, politically sponsored extortions and sheer unpredictability of the public policies are true bottlenecks for the private sector investment, both foreign and domestic. Consequently, economy suffers from low level of investment and job creation, low level of private sector confidence and, as the result, massive amount of capital flight from the country.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Despite all these odds, we must acknowledge the fact that the private sector has constantly been instrumental in the delivery of goods and services at the lowest possible price levels when the presence of government apparatus is as good as non-existent, and even when the armed conflict was at its height.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>3. Civil Society and NGOs</strong></span></div>

<div>

Nepal's civil society and the media don't believe in a long but natural process of the outcome of their activities. The natural role of the civil society or media is to cater the common people with factual information, on the basis of which people form their opinion, and that opinion gets reflected through the ballots. Then comes change through the policies of the mandated government. But, instead, in Nepal they want to be seen as activists and instant impact makers. The NGOs and INGOs strive deliberately to slip-out from the bracket of civil society and claim themselves to be real, grassroots development partners. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The media outlets in general have grown in terms of quantity, quality and reach, whereas NGO activities have become more suspicious and slanted. A large number of INGOs are deeply engaged in spreading this or that religion. . We probably need to re-examine the extent of real contribution of many of such NGOs to the economic growth, development and social harmony of our country.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>4. The Beneficiaries </strong></span></div>

<div>

The common people both as actors and true beneficiaries of the economic growth and development efforts are at complete loss of direction. First, the people who are so far completely deprived of any form of meaningful development are not capable of even to identify and articulate their developmental needs. Let me directly quote from a woman whom I had met at Dehimandu of Baitadi, a year ago. In her early thirties, she looked like of fifties, who on top of a heavy load of fodder was carrying two malnourished kids and a pitcherful of water in her arms.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

When I asked her what did she looked for to ameliorate her sufferings, she first vehemently denied that she had had any suffering and then explained -- she was a happy woman as she could fetch drinking water walking just for 45 minutes whereas she had to spend some one hour in her parental home before marriage, collect fodder from the grassland half an hour away, her two kids out of six she gave birth have, fortunately, survived, her husband who worked in the Indian town of Pithoragarh visits twice a year, her mother-in-law beats her only once or twice a month, she had four cattle and enough land to feed her family for eight months in a year and rest is managed by her husband and his brother. She has plans for sending her kids to nearby school, just two hours of walk, for few years, and then they will follow their father to work in some Indian city. 'I am a happy woman and want nothing more," she emphasized.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

I don't think this story needs any further illustration.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Second, who know what they want, they too don't have access to the authorities or knowledge on how to communicate their demands and concerns. Even if some managed to communicate, the end result may just be the same as being idle, ab initio.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

There is another extreme, where people lately have begun to obstruct the development projects claiming to have absolute ownership of the entire natural resources of their area. The process of participatory development is impeded either way.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>5. The Donors</strong></span></div>

<div>

Unlike in other countries, donors for Nepal's case are imperatively very crucial development actors. It is but natural that the donors, particularly the bilateral ones, have their own interest or agenda in providing the financial assistance to Nepal. The nature of such interest, though, may vary from presenting a mere philanthropic face of the donor in question, influencing in certain policies, providing business to their home companies to increasing diplomatic clout.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

It is the responsibility of Nepal as a nation-state to identify our needs, prioritize them and explore the areas of possible engagements for the donors where their interest may be served without jeopardizing or compromising our own interests. We often degrade ourselves claiming that we cannot afford to be selective or, to say no. May be true. But we definitely can streamline the support and make them to agree to spend in our projects and programmes chosen by the national budget system.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<img alt="Foreign Employment" src="/userfiles/images/CS3%20(Copy).jpg" style="width: 550px; height: 330px; margin-left: 10px; margin-right: 10px;" /></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

For years, we have tried to formulate a functional foreign aid policy but failed to conclusively frame and effectively implement it. Our absorption capacity of foreign assistance has often been below the 'fair' mark and donors seem reluctant to increase and diversify the support mainly due to prolonged political transition and uncertainty coupled with administrative inefficiency. We have often failed to meet the capital expenditure earmarked by our own system that hardly gives incentive to major donors to augment their grant or loan portfolios.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

We often hear not only engagement but of overengaement of the donors in our development process. They are often alleged of directly interfering in policy making, selection and implementation of the projects etc. Many countries bring in their own experts and repatriate larger chunk of their support back home. Discrimination in pay for the same work between the Nepali staff of same qualification and caliber against their consultants is whopping. Probably Nepal has left more vacuum, not doing proper homework in time to make their engagement more fruitful yet unintrusive. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 16px;"><strong>Dynamics and Correlations</strong></span></div>

<div>

Let’snow dwell briefly on a few key dynamics of Nepali economy. I will touch upon only those areas which appear to be inconsistent in pattern, look paradoxical or needed fresh looks and comparisons. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>1. Dynamics of the Human Resource and Migration</strong></span></div>

<div>

Nepal's population growth rate now stands at 1.4 percent per annum according to census 2011. Without going into the boring details of numbers, we can say that some of the development indicators certainly show that we have made very impressive progress in terms of increasing the primary school enrollment, literacy and life expectancy, reducing child and maternal mortality rates, increasing access to health and transport services etc.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

But with regard to human resource development, we are caught in a very awkward position. About one third of the working age population (or about twelve percent of the total population) has out-migrated to foreign employment, mainly in menial jobs. Better educated too, have migrated to developed countries, majority of them with a set mind to permanently settle in the destination countries.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

It is an interesting paradox that migrated unskilled and uneducated youths are sending their entire earning back to Nepal and the remittances thus received have saved Nepali economy for at least a decade now from potentially falling into acute balance of payment crisis. On the contrary, the educated lot is not only migrating but also taking a hefty sum, on an average forex equivalent of about 35 billion rupees every year, from the national coffers towards tuition, travel and accommodation costs.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

In a rough calculation, to create a university graduate with sixteen years of education in private institution at present prices costs the nation between 5 to 6 million rupees. And, the return to the nation is clearly zero when one migrates never to come back. It is another paradox that the poor country like Nepal is investing so heavily in human resource to be used solely by the developed countries. The cost-benefit comparison shows that after such a big investment in education, it is unfeasible for them to stay in Nepal and get the cost returned given the lack of opportunities and relatively unattractive pays here.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Then, left here in Nepal are true mediocres, who have spent less, studying in community schools, compelled to be contended with low rate of return and perform far below than the average. Nepali civil service is the true mirror of this phenomenon. If the trend of migration is not reversed, very soon Nepal will lack the required human resource of both low and high end skills. This is likely to have serious repercussion in national output. A trend is already visible in sectors like metal and construction works.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<img alt="Direction of Foreign Trade" src="/userfiles/images/CS4%20(Copy).jpg" style="width: 550px; height: 429px; margin-left: 10px; margin-right: 10px;" /></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>2. Dynamics of Foreign Trade and Remittances</strong></span></div>

<div>

Nepal's trade deficit stood at scary level of 500 billion rupees in the last fiscal year (2012/13). Official figures show that export to import ratio was 1:6, whereas unofficial estimates suggest that such ratio should stand at 1:10. The accompanying table is self explanatory.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

In the last FY, Nepal received about 435 billion equivalent of remittances from the migrant workers. This definitely has put Nepal in comfortable level of forex reserve. But, a comparison of trade and remittance data suggests that our economy is heading to a very dangerous trend of the Dutch Disease like effect. Our consumption has been fueled by the remittance income of the households, which in turn is widening the export-import gap. Our productive sector is paralyzed for lack of power, human resource and investment. Our imports are largely consumables, perishables but hardly the production inputs. This apparently is unsustainable, dangerous trend. We need to re-identify Nepali goods that can have comparative and competitive advantage in the export market. At the same time, we must be able to diversify both export and import trade.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>3. Dynamics of Growth and Poverty</strong></span></div>

<div>

Nepal's average annual GDP growth rate during the last fifteen years has remained barely at 3.5 percent level. But, in the same period, the headcount poverty, the percentage of the population living below $1 dollar a day poverty line at PPP has unbelievably reduced from 58 percent in 1996 to 25 percent in 2011. What we are effectively saying here is that the poverty can be reduced without growth. In other words, we are challenging the existing theories that correlate growth and poverty and suggesting a completely new economic paradigm on both growth and poverty reduction. This is impossible. The government's development literature attributes this as the effect of the increased inflow of the remittances. Again, if that is the case too, we are saying that the remittances do not contribute to the economic growth but reduce poverty. This is equivalent to proposing an absolutely new economic theory.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

In countries like India and Argentina some 30 percent people still live under the poverty line. Mexico has 28 percent people under this magic line. It appears that we are very fast approaching to the United States which still has 15.1 percent people living under the poverty line, according to the World Bank data of 2011. All these are impossible and counter-intuitive arguments and one single conclusion of this is: what we are saying is not credible. On the one hand, we are saying that graduating a country from the least developed to a developing one is a highly ambitious enterprise, on the other our poverty data shows that we are already in far higher position than many of G-20 countries.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>4. Investment and Infrastructure</strong></span></div>

<div>

The private sector investment both domestic and FDI are in declining trend. The foreign direct investment of Rs. 9.08 billion was recorded in FY 2012/13compared to Rs. 9.20 billion in the previous year. The intent of investing about Rs. 39 billion was proposed by domestic entrepreneurs in the same year, which is less by some seven percent than the previous year. Apart from this, an investment of Rs 100 billion has been proposed for the hydel projects expected to be completed in next five years.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

One of the very encouraging developments is that the private sector has more aggressively come forward to invest in infrastructure than ever, not only in power but also in the telecommunications, surface transportation and airports. There are a number of large J-V projects in hydropower like Upper Karnali, Upper Seti and Arun III, at different stages of development. Yet, they have constantly been victim of political bickerings and protracted decision making process in the bureaucracy.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/CS1%20(Copy)(1).jpg" style="width: 550px; height: 367px; margin-left: 10px; margin-right: 10px;" /></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Very shaky political climate is main distraction to investment, both domestic and foreign.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>5. Agriculture and Manufacturing</strong></span></div>

<div>

Our experience suggests that Nepal is not faring well in the manufacturing. Many products we tried could not compete with Indian and Chinese goods that are in instant supply and cheaper for the reasons of mass production and use mostly of their own raw materials. But on the contrary, Nepal has fared well in our niche products like hand-spun dhaaka and pashmina, handicrafts and herbs where there is our backward link in production and possibility of substantive value addition.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The manufacturing industries that use Nepali agricultural products have seemingly given better returns to investment. The commercialization of agriculture itself presents real prospects for investment, perhaps in a scale thus far not even imagined of. Off-season farming of cash-crops and commercial farming of valuable herbs can open new avenues in the agriculture sector. Added road links to provide market access should be able to attract new investment for processing, phyto-sanitation and storage facilities. But, we often get carried away by the documentary camouflages like Agriculture Perspective Plan (APP), which presented every possible good plan for agricultural growth without any mention about the land where farming would be done. This was truly a plan made to farm in the air. Just an example.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>6. The Service Sector & Growth Linkage</strong></span></div>

<div>

Two sectors, financial services and tourism have exhibited very promising trend both in terms of attracting substantial amount of investment and promising good rate of returns. The financial sector now mobilizes about Rs 1.1 trillion of deposits and Rs. 0.9 trillion as loans and investments. The growth in the sub-sectors of insurance, stocks and commodities has also been impressive. But the hard fact is, Nepal's entire banking sector even jointly doesn't have liquidity enough to finance a medium-scale hydro project of say of 200 MW. Similar is the situation of insurance companies to provide insurance cover to these projects if they opted to insure. We don't have a domestic reinsurer, yet.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Areas like transportation services have also expanded, along with the increased road networks. The tourism infrastructure is growing steadily. Health and education services by now have national reach due to private sector investment. But the issue here is: how do we make the expansion of these sectors contributory to the overall economic growth of the country? Anomalies like in these sectors have rather added new problems. For example, the over exposure of the banking credit in the real-estate has fueled inflation, created large portfolio of NPA in the industry and put the balance-sheet of a number of banks in a very bad shape for a number of years.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The transportation facilities can contribute more if they provided easier market access to the products and supported supply of inputs to increase the production and add value to them. But, largely, the scenario is just opposite.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>7. Choice between Improved Subsistence & Prosperity</strong></span></div>

<div>

There has been virtual explosion in small scale development initiatives like solar and micro hydro for rural electrification, NGO-led rights based development and awareness campaigns, literacy classes, skill development and self-employment schemes, community or gender-focused empowerment programmes etc. Policies of reservation, inclusion and positive discrimination are now widely debated. These definitely are good things. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

But we need to link these activities with our main objective. If our prime aim is a little improvement in the bare subsistence life-style and help reduce abject poverty, these are definitely the ways we should invest and focus on. But if our aim is tangible economic growth that can also compensate to the lost opportunity of decades, we need higher degree of commitment, massive investment and multi-stakeholder engagement at all possible levels, as we discussed about. By now, it is apparent that these small things may be beautiful in facilitating poorest of the poor to live relatively a better life, but seldom enough to effectively speed-up the economic growth and overall prosperity and well-being of the entire population. When we can uplift the living standard of every citizen, universally ensure education and employment, issues of inclusion and reservations automatically become redundant. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<img alt="Choice" src="/userfiles/images/CD2%20(Copy).jpg" style="width: 550px; height: 413px; margin-left: 10px; margin-right: 10px;" /></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 16px;"><strong>Engagement: Process & Paradigm</strong></span></div>

<div>

'Engaging Overall Partners' is a great concept and also an absolute imperative. But engaging multi-stakeholders with varying, often conflicting, interests is an equally challenging proposition. It perhaps requires a different development culture than Nepal is practicing now. We need both formal and informal common forums, factual information and access to them, effective communication amongst all stakeholders in multitude of directions, reasonable level of credible independent research to ascertain what is working and what is not and, of course, a unity of purpose at the macro level of objectives. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Some key components that can be instrumental in enhancing such engagement can be as follows:</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>1. Discourse</strong></span></div>

<div>

Nepal utterly lacks any form of meaningful discourse, at any level on economic, financial and developmental issues, except for some media reports and limited number of seminars that take place, here and there. Such discourses should have taken place at three different arenas -- the political parties, policy making units and the academia. And, they should.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Since the political parties are the one who govern the country, the economic policy of each major one of them is important tool to make people understand their means and ends of the economic growth and development. Such policy of each party, ideally, should be framed through fully democratic debate at all levels of the respective party organizations; and reflected in their manifestoes. But, this is not at all the case. Except for a couple of leaders in each major party who understand economic issues, the entire outfits are virtually illiterate about the economy, its components and trends. Worst of all, none of these parties have understood the importance of such debate and need to initiate them sooner than later.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

At the policy making level, trained economists are rare species. A couple of recent finance ministers, for example, were undergrads in subjects other than economics. Bureaucrats have more incentive in appeasing their bosses in any possible way but professionalism. They lack refreshment trainings, more so in economic issues. The redundancy of their rusted ideas gets amply reflected in the so-called new but essentially archaic policies. It is one of the main reasons that our economic policies seldom work.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Both of the deficiencies in political and bureaucratic levels should have been bridged by the discourse at academic level. But, unfortunately, in Nepal such discourse is completely absent. A few academics who have made some name as economists have limited themselves in the role of consultants to INGOs and impartial viewpoints about national economy are non-existent. The reluctance of newer universities to institute the department of economics is indicative enough to explain the predicament.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Discourses at stakeholders' level, on the topics suitably designed to them are another striking need. At the donors' level, they seem to have instituted a loose network, but its effectiveness as a debate forum on the core economic issues is still beyond the public knowledge.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>2. Research</strong></span></div>

<div>

For meaningful engagement at any level, credible data are the primary need. The factual information only can ascertain the scope of participation for each stakeholder. But, whenever we try to talk about any aspect of Nepali economy, we immediately loose thread for lack of proper data and absence of conclusions drawn out by properly analyzing them. As mentioned above, we have contradictory and unbelievable or just tentative figures even on cardinal data like GDP, inflation, unemployment and trade. All comparison and correlation conclusions, like I made above, are largely heuristic. We have no option citing whatever the government agencies like the National Planning Commission, Nepal Rastra Bank or Finance Ministry cook in the name of research and analysis. The nation hardly invests anything in research. There are not independent, credible and well-equipped institutions to carryout research in multi-dimensional aspects of the economy and its trends. Such large scale researches need substantial resources and experts right from the stage of research design to econometric analysis and interpretation of those results. There must be somebody to invest on them.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>3. Reform</strong></span></div>

<div>

The policy and institutional reforms are other important areas that ensure participatory engagement among the development actors. The continuous process of policy reforms provide opportunity to accommodate the emerging needs, practically realized in the development processes at different levels. The institutional reforms increase the functionality of the actors and replicability of the good practices. Nepal also greatly lags behind in undertaking reforms that are due for long time. Some multi-donor sectoral approaches (SAps) in education and health sectors have delivered impressive results. If similar policy as well as institutional frameworks can be extended to include other possible actors in more sectors, that is likely to increase the portfolio efficiency. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>4. Streamlining</strong></span></div>

<div>

It is important to understand, when we engage multiple stakeholders, it is natural to have varying interests, priorities, methodologies and objectives to come to fore. Without streamlining them, the national objective of economic prosperity is impossible to achieve. Extensive exercises of benchmarking, clustering, grading and ranking are the necessary part of this process. This can greatly reduce the duplication or omission of many of development endeavours; thereby increase the allocative efficiency of resources. A national focal point, a functional unit, not a generic large structure like a ministry, is internationally adopted practice. At times, when the government agencies try to do it, there are instances of conflicts between the different actors. Therefore, such tasks could be outsourced to some independent professional entity with established, proven credibility.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>5. Good Faith</strong></span></div>

<div>

All forms of engagements are only possible if the actors are committed to support in good faith on single objectives of economic growth and development of Nepal. The source of good faith is the spirit of democracy that respects the plurality of views, culture of agreeing to disagree and readiness to be partner in the process than to be a savior or ruler. We all have our interests. Sacrifice of a small portion of it by each actor might create a large space for engagement and cooperation and also help serve our own interests better while helping others to serve their own. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<em> (Based on paper presented by the author, in IVAAN seminar, 7th Dec 2013 in Kathmandu.)</em></div>',

'status' => true,

'publish_date' => '0000-00-00',

'created' => '2014-01-11 00:00:00',

'modified' => '0000-00-00 00:00:00',

'keywords' => 'new business age cover story news & articles, cover story news & articles from new business age nepal, cover story headlines from nepal, current and latest cover story news from nepal, economic news from nepal, nepali cover story economic news and events, ongoing cover story news of nepal',

'description' => 'Multi-stakeholder Approach is the recent buzzword in development literature. How can Nepal use this approach? Achyut Wagle analyses the challenges and opportunities.',

'sortorder' => '587',

'feature_article' => true,

'user_id' => '0',

'image1' => null,

'image2' => null,

'image3' => null,

'image4' => null

),

'MagazineIssue' => array(

'id' => '472',

'image' => 'small_1389264715.jpg',

'sortorder' => '367',

'published' => true,

'created' => '2014-01-09 03:52:22',

'modified' => null,

'title' => 'Cover Story',

'publish_date' => '2014-01-01',

'parent_id' => '460',

'homepage' => false,

'user_id' => '0'

),

'MagazineCategory' => array(

'id' => null,

'title' => null,

'sortorder' => null,

'status' => null,

'created' => null,

'homepage' => null,

'modified' => null

),

'User' => array(

'password' => '*****',

'id' => null,

'user_detail_id' => null,

'group_id' => null,

'username' => null,

'name' => null,

'email' => null,

'address' => null,

'gender' => null,

'access' => null,

'phone' => null,

'access_type' => null,

'activated' => null,

'sortorder' => null,

'published' => null,

'created' => null,

'last_login' => null,

'ip' => null

),

'MagazineArticleComment' => array(),

'MagazineView' => array(

(int) 0 => array(

[maximum depth reached]

)

)

),

'current_user' => null,

'logged_in' => false

)

$magazineArticle = array(

'MagazineArticle' => array(

'id' => '613',

'magazine_issue_id' => '472',

'magazine_category_id' => '0',

'title' => 'Partners In Economic Growth',

'image' => null,

'short_content' => null,

'content' => '<div>

<img alt="Cover Story" src="/userfiles/images/CS%20(Copy).jpg" style="width: 550px; height: 540px; margin-left: 10px; margin-right: 10px;" /></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 16px;">Multi-stakeholder Approach is the recent buzzword in development literature. How can Nepal use this approach? <strong>Achyut Wagle </strong>analyses the challenges and opportunities.</span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

When we say 'engaging development actors' we are talking about hierarchical operational levels like local, district, sub-regional, regional, national, international and global, where each of these levels form a complex matrix of actual actors primarily from five sectors -- the public or government, private or business, civil society, actual beneficiaries or common people and, development partners (donors). </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The economic growth is only possible through multidimensional interactions among these different groups of actors that are defined by the recent development literature as multi-stakeholder approach of development. The scope and limitation of the roles of each of these and conflicts and/or complementarities of the interests of these actors, singly or jointly, determines both the scale and the speed of the economic growth of any country, including Nepal. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

However, there is a problem in the definitional level, that is, whether all players in Nepal could be covered by these five categories of development actors mentioned above. Take for example Nepal's political parties who on their own right want to be the development actors, whereas their role and influence in development domain should either come through the public sector (for those who win the election and form the government) or only as the common people or the beneficiary (until they win the next election). The face of the civil society, if it has any, is not different from that of the political parties. In international practice, donors do not figure out with separate identities, who in Nepal's case appear even more quintessential actors. These distortions have serious implications both in engaging the development actors in their due roles and also attaining the ultimate results of our development endeavours. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 16px;"><strong>Actors</strong></span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>1. The Government</strong></span></div>

<div>

It is obvious that we need government for governance, hopefully a good governance. Although Nepal is not an exception among the least developed nations that face the crisis of governance, but one additional dimension in our case is we persistently face deficiency of democracy, perhaps more acutely at present. Nepal's politics during the last six decades of modern history has invariably been dominated by the dictatorial forces of some form that didn't believe in pluralistic, competitive democracy. This has been the main source of crisis of governance in general, manifested in the form of rule of force than rule of law, poor growth of institutions and their effectiveness, haphazardly conceived and weakly implemented policies, misuse of the state power by the powerfuls, strong nexus between the crime and law enforcement, utter lack of transparency and rampant corruption in public expenditure, rise of business syndicates and, worst of all, pervasive and persistent impunity. And, the list can on, and on.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

We don't have elected local governments at the local and district levels for last one decade, for no tangible reason for this vacuum, except for the height of irresponsibility and imperviousness of the political actors of the country. It should have in fact been the first priority of all particularly after the signing of Comprehensive Peace Treaty seven years ago; as the local governments would have been the best channels to deliver the much touted about peace dividend, many of the economic rights and delivery of the public services at the grassroots. Above all, it would have provided the people at the grassroots with direct access to the state mechanism. One can only imagine at this point, how many of new generation of leaders this process would have produced and how much would it have facilitated the process of proposed federalization of Nepal.</div>

<div>

Nepal never created democratic government institutions at sub-regional or regional levels. We have bureaucratic arrangements like regional administrators who virtually have no role in economic planning and development except for that of official messengers.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<img alt="The Engagement Matrix" src="/userfiles/images/CS2%20(Copy).jpg" style="width: 550px; height: 307px; margin-left: 10px; margin-right: 10px;" /></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

At the national level, we have Himalayan scale of policy confusions at development governance. We still have National Planning Commission (NPC) located inside the high walls of Sigha Durbar, that mercifully distributes development to the people of far and wide corners of Nepal. We still believe that the people who live in NPC as if have divine senses to understand the exact development needs of the people living at Tinker and Olangchung Gola and ability to address them from here. The duplication of the roles between the finance ministry and NPC, the constant squabbles and ego-clashes of the mandarins in them is staple national drama. The independence of central bank has always been a mirage, as we saw ten governors in Nepal Rastra Bank in as many years. We never had and, nor will have the possibility of implementing an independent monetary policy of our own in foreseeable future due to 'pegging' of Nepali currency with the Indian Rupee.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

At the international level, Nepal is gradually losing its credibility as a viable economy. We have not been able to organize the Nepal Development Forum, to interact with our international development partners, for the last one decade. Our ability to communicate about our needs with them and prioritize development areas to streamline their support has substantially reduced. The torch-bearers of our economic diplomacy are the political nominees typified, for example, by the recently sacked Nepali ambassador to Qatar. We may talk about FDI, but it has even stopped trickling in. We have also failed to introduce a functional mechanism to make sure that all official foreign assistance is spent through our budget, despite the fact that many of the donors are in favour of such a system.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>2. The Private Sector</strong></span></div>

<div>

The post-1990 marked an era that tried to put the private sector in the driving seat of economic growth. The policies of liberalization, privatization and legal as well as institutional reforms initiated by the first elected government after reinstatement of democracy brought about substantial positive changes, the impact of which has withstood violent conflict of a decade. Private airlines, large private sector banks, private hospitals, multiple universities, private investment in communication, information technology and hydropower, and private participation in building infrastructures like roads and irrigation facilities are some of the exemplary outcomes of these policies.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

But this encouraging trend was abruptly truncated by the armed conflict waged by the Maoists and, after seven long years after cessation of hostilities too, there is no certain sign of putting the policy of private-sector-led growth back on track. The political mayhem we are witnessing even after the second Constituent Assembly elections last month is even more disgusting to say the least.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Needless to say, three preconditions for private sector actors to come forward to contribute to economic growth are: ensured private property rights, an appropriate business climate that encourages investment and a predictable policy regime that provides a reasonable time horizon for conceptualizing, executing, operating and if needed closing of the businesses without being unnecessarily anxious about the safety of, as well as, return from the investment.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

But, the greatest challenge to all of these aspects not only comes at the operational level but at the level of the very philosophy of the strongest of the political forces of Nepal. Confiscation of the private property, politically patronized trade unions disturbing the industrial atmosphere, politically sponsored extortions and sheer unpredictability of the public policies are true bottlenecks for the private sector investment, both foreign and domestic. Consequently, economy suffers from low level of investment and job creation, low level of private sector confidence and, as the result, massive amount of capital flight from the country.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Despite all these odds, we must acknowledge the fact that the private sector has constantly been instrumental in the delivery of goods and services at the lowest possible price levels when the presence of government apparatus is as good as non-existent, and even when the armed conflict was at its height.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>3. Civil Society and NGOs</strong></span></div>

<div>

Nepal's civil society and the media don't believe in a long but natural process of the outcome of their activities. The natural role of the civil society or media is to cater the common people with factual information, on the basis of which people form their opinion, and that opinion gets reflected through the ballots. Then comes change through the policies of the mandated government. But, instead, in Nepal they want to be seen as activists and instant impact makers. The NGOs and INGOs strive deliberately to slip-out from the bracket of civil society and claim themselves to be real, grassroots development partners. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The media outlets in general have grown in terms of quantity, quality and reach, whereas NGO activities have become more suspicious and slanted. A large number of INGOs are deeply engaged in spreading this or that religion. . We probably need to re-examine the extent of real contribution of many of such NGOs to the economic growth, development and social harmony of our country.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>4. The Beneficiaries </strong></span></div>

<div>

The common people both as actors and true beneficiaries of the economic growth and development efforts are at complete loss of direction. First, the people who are so far completely deprived of any form of meaningful development are not capable of even to identify and articulate their developmental needs. Let me directly quote from a woman whom I had met at Dehimandu of Baitadi, a year ago. In her early thirties, she looked like of fifties, who on top of a heavy load of fodder was carrying two malnourished kids and a pitcherful of water in her arms.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

When I asked her what did she looked for to ameliorate her sufferings, she first vehemently denied that she had had any suffering and then explained -- she was a happy woman as she could fetch drinking water walking just for 45 minutes whereas she had to spend some one hour in her parental home before marriage, collect fodder from the grassland half an hour away, her two kids out of six she gave birth have, fortunately, survived, her husband who worked in the Indian town of Pithoragarh visits twice a year, her mother-in-law beats her only once or twice a month, she had four cattle and enough land to feed her family for eight months in a year and rest is managed by her husband and his brother. She has plans for sending her kids to nearby school, just two hours of walk, for few years, and then they will follow their father to work in some Indian city. 'I am a happy woman and want nothing more," she emphasized.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

I don't think this story needs any further illustration.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Second, who know what they want, they too don't have access to the authorities or knowledge on how to communicate their demands and concerns. Even if some managed to communicate, the end result may just be the same as being idle, ab initio.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

There is another extreme, where people lately have begun to obstruct the development projects claiming to have absolute ownership of the entire natural resources of their area. The process of participatory development is impeded either way.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>5. The Donors</strong></span></div>

<div>

Unlike in other countries, donors for Nepal's case are imperatively very crucial development actors. It is but natural that the donors, particularly the bilateral ones, have their own interest or agenda in providing the financial assistance to Nepal. The nature of such interest, though, may vary from presenting a mere philanthropic face of the donor in question, influencing in certain policies, providing business to their home companies to increasing diplomatic clout.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

It is the responsibility of Nepal as a nation-state to identify our needs, prioritize them and explore the areas of possible engagements for the donors where their interest may be served without jeopardizing or compromising our own interests. We often degrade ourselves claiming that we cannot afford to be selective or, to say no. May be true. But we definitely can streamline the support and make them to agree to spend in our projects and programmes chosen by the national budget system.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<img alt="Foreign Employment" src="/userfiles/images/CS3%20(Copy).jpg" style="width: 550px; height: 330px; margin-left: 10px; margin-right: 10px;" /></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

For years, we have tried to formulate a functional foreign aid policy but failed to conclusively frame and effectively implement it. Our absorption capacity of foreign assistance has often been below the 'fair' mark and donors seem reluctant to increase and diversify the support mainly due to prolonged political transition and uncertainty coupled with administrative inefficiency. We have often failed to meet the capital expenditure earmarked by our own system that hardly gives incentive to major donors to augment their grant or loan portfolios.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

We often hear not only engagement but of overengaement of the donors in our development process. They are often alleged of directly interfering in policy making, selection and implementation of the projects etc. Many countries bring in their own experts and repatriate larger chunk of their support back home. Discrimination in pay for the same work between the Nepali staff of same qualification and caliber against their consultants is whopping. Probably Nepal has left more vacuum, not doing proper homework in time to make their engagement more fruitful yet unintrusive. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 16px;"><strong>Dynamics and Correlations</strong></span></div>

<div>

Let’snow dwell briefly on a few key dynamics of Nepali economy. I will touch upon only those areas which appear to be inconsistent in pattern, look paradoxical or needed fresh looks and comparisons. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>1. Dynamics of the Human Resource and Migration</strong></span></div>

<div>

Nepal's population growth rate now stands at 1.4 percent per annum according to census 2011. Without going into the boring details of numbers, we can say that some of the development indicators certainly show that we have made very impressive progress in terms of increasing the primary school enrollment, literacy and life expectancy, reducing child and maternal mortality rates, increasing access to health and transport services etc.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

But with regard to human resource development, we are caught in a very awkward position. About one third of the working age population (or about twelve percent of the total population) has out-migrated to foreign employment, mainly in menial jobs. Better educated too, have migrated to developed countries, majority of them with a set mind to permanently settle in the destination countries.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

It is an interesting paradox that migrated unskilled and uneducated youths are sending their entire earning back to Nepal and the remittances thus received have saved Nepali economy for at least a decade now from potentially falling into acute balance of payment crisis. On the contrary, the educated lot is not only migrating but also taking a hefty sum, on an average forex equivalent of about 35 billion rupees every year, from the national coffers towards tuition, travel and accommodation costs.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

In a rough calculation, to create a university graduate with sixteen years of education in private institution at present prices costs the nation between 5 to 6 million rupees. And, the return to the nation is clearly zero when one migrates never to come back. It is another paradox that the poor country like Nepal is investing so heavily in human resource to be used solely by the developed countries. The cost-benefit comparison shows that after such a big investment in education, it is unfeasible for them to stay in Nepal and get the cost returned given the lack of opportunities and relatively unattractive pays here.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Then, left here in Nepal are true mediocres, who have spent less, studying in community schools, compelled to be contended with low rate of return and perform far below than the average. Nepali civil service is the true mirror of this phenomenon. If the trend of migration is not reversed, very soon Nepal will lack the required human resource of both low and high end skills. This is likely to have serious repercussion in national output. A trend is already visible in sectors like metal and construction works.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<img alt="Direction of Foreign Trade" src="/userfiles/images/CS4%20(Copy).jpg" style="width: 550px; height: 429px; margin-left: 10px; margin-right: 10px;" /></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>2. Dynamics of Foreign Trade and Remittances</strong></span></div>

<div>

Nepal's trade deficit stood at scary level of 500 billion rupees in the last fiscal year (2012/13). Official figures show that export to import ratio was 1:6, whereas unofficial estimates suggest that such ratio should stand at 1:10. The accompanying table is self explanatory.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

In the last FY, Nepal received about 435 billion equivalent of remittances from the migrant workers. This definitely has put Nepal in comfortable level of forex reserve. But, a comparison of trade and remittance data suggests that our economy is heading to a very dangerous trend of the Dutch Disease like effect. Our consumption has been fueled by the remittance income of the households, which in turn is widening the export-import gap. Our productive sector is paralyzed for lack of power, human resource and investment. Our imports are largely consumables, perishables but hardly the production inputs. This apparently is unsustainable, dangerous trend. We need to re-identify Nepali goods that can have comparative and competitive advantage in the export market. At the same time, we must be able to diversify both export and import trade.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>3. Dynamics of Growth and Poverty</strong></span></div>

<div>

Nepal's average annual GDP growth rate during the last fifteen years has remained barely at 3.5 percent level. But, in the same period, the headcount poverty, the percentage of the population living below $1 dollar a day poverty line at PPP has unbelievably reduced from 58 percent in 1996 to 25 percent in 2011. What we are effectively saying here is that the poverty can be reduced without growth. In other words, we are challenging the existing theories that correlate growth and poverty and suggesting a completely new economic paradigm on both growth and poverty reduction. This is impossible. The government's development literature attributes this as the effect of the increased inflow of the remittances. Again, if that is the case too, we are saying that the remittances do not contribute to the economic growth but reduce poverty. This is equivalent to proposing an absolutely new economic theory.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

In countries like India and Argentina some 30 percent people still live under the poverty line. Mexico has 28 percent people under this magic line. It appears that we are very fast approaching to the United States which still has 15.1 percent people living under the poverty line, according to the World Bank data of 2011. All these are impossible and counter-intuitive arguments and one single conclusion of this is: what we are saying is not credible. On the one hand, we are saying that graduating a country from the least developed to a developing one is a highly ambitious enterprise, on the other our poverty data shows that we are already in far higher position than many of G-20 countries.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>4. Investment and Infrastructure</strong></span></div>

<div>

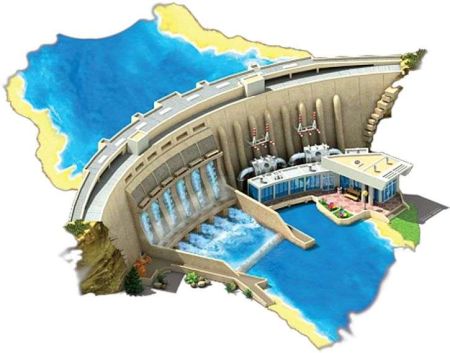

The private sector investment both domestic and FDI are in declining trend. The foreign direct investment of Rs. 9.08 billion was recorded in FY 2012/13compared to Rs. 9.20 billion in the previous year. The intent of investing about Rs. 39 billion was proposed by domestic entrepreneurs in the same year, which is less by some seven percent than the previous year. Apart from this, an investment of Rs 100 billion has been proposed for the hydel projects expected to be completed in next five years.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

One of the very encouraging developments is that the private sector has more aggressively come forward to invest in infrastructure than ever, not only in power but also in the telecommunications, surface transportation and airports. There are a number of large J-V projects in hydropower like Upper Karnali, Upper Seti and Arun III, at different stages of development. Yet, they have constantly been victim of political bickerings and protracted decision making process in the bureaucracy.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/CS1%20(Copy)(1).jpg" style="width: 550px; height: 367px; margin-left: 10px; margin-right: 10px;" /></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Very shaky political climate is main distraction to investment, both domestic and foreign.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>5. Agriculture and Manufacturing</strong></span></div>

<div>

Our experience suggests that Nepal is not faring well in the manufacturing. Many products we tried could not compete with Indian and Chinese goods that are in instant supply and cheaper for the reasons of mass production and use mostly of their own raw materials. But on the contrary, Nepal has fared well in our niche products like hand-spun dhaaka and pashmina, handicrafts and herbs where there is our backward link in production and possibility of substantive value addition.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The manufacturing industries that use Nepali agricultural products have seemingly given better returns to investment. The commercialization of agriculture itself presents real prospects for investment, perhaps in a scale thus far not even imagined of. Off-season farming of cash-crops and commercial farming of valuable herbs can open new avenues in the agriculture sector. Added road links to provide market access should be able to attract new investment for processing, phyto-sanitation and storage facilities. But, we often get carried away by the documentary camouflages like Agriculture Perspective Plan (APP), which presented every possible good plan for agricultural growth without any mention about the land where farming would be done. This was truly a plan made to farm in the air. Just an example.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>6. The Service Sector & Growth Linkage</strong></span></div>

<div>

Two sectors, financial services and tourism have exhibited very promising trend both in terms of attracting substantial amount of investment and promising good rate of returns. The financial sector now mobilizes about Rs 1.1 trillion of deposits and Rs. 0.9 trillion as loans and investments. The growth in the sub-sectors of insurance, stocks and commodities has also been impressive. But the hard fact is, Nepal's entire banking sector even jointly doesn't have liquidity enough to finance a medium-scale hydro project of say of 200 MW. Similar is the situation of insurance companies to provide insurance cover to these projects if they opted to insure. We don't have a domestic reinsurer, yet.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Areas like transportation services have also expanded, along with the increased road networks. The tourism infrastructure is growing steadily. Health and education services by now have national reach due to private sector investment. But the issue here is: how do we make the expansion of these sectors contributory to the overall economic growth of the country? Anomalies like in these sectors have rather added new problems. For example, the over exposure of the banking credit in the real-estate has fueled inflation, created large portfolio of NPA in the industry and put the balance-sheet of a number of banks in a very bad shape for a number of years.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The transportation facilities can contribute more if they provided easier market access to the products and supported supply of inputs to increase the production and add value to them. But, largely, the scenario is just opposite.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>7. Choice between Improved Subsistence & Prosperity</strong></span></div>

<div>

There has been virtual explosion in small scale development initiatives like solar and micro hydro for rural electrification, NGO-led rights based development and awareness campaigns, literacy classes, skill development and self-employment schemes, community or gender-focused empowerment programmes etc. Policies of reservation, inclusion and positive discrimination are now widely debated. These definitely are good things. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

But we need to link these activities with our main objective. If our prime aim is a little improvement in the bare subsistence life-style and help reduce abject poverty, these are definitely the ways we should invest and focus on. But if our aim is tangible economic growth that can also compensate to the lost opportunity of decades, we need higher degree of commitment, massive investment and multi-stakeholder engagement at all possible levels, as we discussed about. By now, it is apparent that these small things may be beautiful in facilitating poorest of the poor to live relatively a better life, but seldom enough to effectively speed-up the economic growth and overall prosperity and well-being of the entire population. When we can uplift the living standard of every citizen, universally ensure education and employment, issues of inclusion and reservations automatically become redundant. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<img alt="Choice" src="/userfiles/images/CD2%20(Copy).jpg" style="width: 550px; height: 413px; margin-left: 10px; margin-right: 10px;" /></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 16px;"><strong>Engagement: Process & Paradigm</strong></span></div>

<div>

'Engaging Overall Partners' is a great concept and also an absolute imperative. But engaging multi-stakeholders with varying, often conflicting, interests is an equally challenging proposition. It perhaps requires a different development culture than Nepal is practicing now. We need both formal and informal common forums, factual information and access to them, effective communication amongst all stakeholders in multitude of directions, reasonable level of credible independent research to ascertain what is working and what is not and, of course, a unity of purpose at the macro level of objectives. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Some key components that can be instrumental in enhancing such engagement can be as follows:</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>1. Discourse</strong></span></div>

<div>

Nepal utterly lacks any form of meaningful discourse, at any level on economic, financial and developmental issues, except for some media reports and limited number of seminars that take place, here and there. Such discourses should have taken place at three different arenas -- the political parties, policy making units and the academia. And, they should.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Since the political parties are the one who govern the country, the economic policy of each major one of them is important tool to make people understand their means and ends of the economic growth and development. Such policy of each party, ideally, should be framed through fully democratic debate at all levels of the respective party organizations; and reflected in their manifestoes. But, this is not at all the case. Except for a couple of leaders in each major party who understand economic issues, the entire outfits are virtually illiterate about the economy, its components and trends. Worst of all, none of these parties have understood the importance of such debate and need to initiate them sooner than later.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

At the policy making level, trained economists are rare species. A couple of recent finance ministers, for example, were undergrads in subjects other than economics. Bureaucrats have more incentive in appeasing their bosses in any possible way but professionalism. They lack refreshment trainings, more so in economic issues. The redundancy of their rusted ideas gets amply reflected in the so-called new but essentially archaic policies. It is one of the main reasons that our economic policies seldom work.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Both of the deficiencies in political and bureaucratic levels should have been bridged by the discourse at academic level. But, unfortunately, in Nepal such discourse is completely absent. A few academics who have made some name as economists have limited themselves in the role of consultants to INGOs and impartial viewpoints about national economy are non-existent. The reluctance of newer universities to institute the department of economics is indicative enough to explain the predicament.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Discourses at stakeholders' level, on the topics suitably designed to them are another striking need. At the donors' level, they seem to have instituted a loose network, but its effectiveness as a debate forum on the core economic issues is still beyond the public knowledge.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>2. Research</strong></span></div>

<div>

For meaningful engagement at any level, credible data are the primary need. The factual information only can ascertain the scope of participation for each stakeholder. But, whenever we try to talk about any aspect of Nepali economy, we immediately loose thread for lack of proper data and absence of conclusions drawn out by properly analyzing them. As mentioned above, we have contradictory and unbelievable or just tentative figures even on cardinal data like GDP, inflation, unemployment and trade. All comparison and correlation conclusions, like I made above, are largely heuristic. We have no option citing whatever the government agencies like the National Planning Commission, Nepal Rastra Bank or Finance Ministry cook in the name of research and analysis. The nation hardly invests anything in research. There are not independent, credible and well-equipped institutions to carryout research in multi-dimensional aspects of the economy and its trends. Such large scale researches need substantial resources and experts right from the stage of research design to econometric analysis and interpretation of those results. There must be somebody to invest on them.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>3. Reform</strong></span></div>

<div>

The policy and institutional reforms are other important areas that ensure participatory engagement among the development actors. The continuous process of policy reforms provide opportunity to accommodate the emerging needs, practically realized in the development processes at different levels. The institutional reforms increase the functionality of the actors and replicability of the good practices. Nepal also greatly lags behind in undertaking reforms that are due for long time. Some multi-donor sectoral approaches (SAps) in education and health sectors have delivered impressive results. If similar policy as well as institutional frameworks can be extended to include other possible actors in more sectors, that is likely to increase the portfolio efficiency. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>4. Streamlining</strong></span></div>

<div>

It is important to understand, when we engage multiple stakeholders, it is natural to have varying interests, priorities, methodologies and objectives to come to fore. Without streamlining them, the national objective of economic prosperity is impossible to achieve. Extensive exercises of benchmarking, clustering, grading and ranking are the necessary part of this process. This can greatly reduce the duplication or omission of many of development endeavours; thereby increase the allocative efficiency of resources. A national focal point, a functional unit, not a generic large structure like a ministry, is internationally adopted practice. At times, when the government agencies try to do it, there are instances of conflicts between the different actors. Therefore, such tasks could be outsourced to some independent professional entity with established, proven credibility.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size: 14px;"><strong>5. Good Faith</strong></span></div>

<div>

All forms of engagements are only possible if the actors are committed to support in good faith on single objectives of economic growth and development of Nepal. The source of good faith is the spirit of democracy that respects the plurality of views, culture of agreeing to disagree and readiness to be partner in the process than to be a savior or ruler. We all have our interests. Sacrifice of a small portion of it by each actor might create a large space for engagement and cooperation and also help serve our own interests better while helping others to serve their own. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<em> (Based on paper presented by the author, in IVAAN seminar, 7th Dec 2013 in Kathmandu.)</em></div>',

'status' => true,

'publish_date' => '0000-00-00',

'created' => '2014-01-11 00:00:00',

'modified' => '0000-00-00 00:00:00',

'keywords' => 'new business age cover story news & articles, cover story news & articles from new business age nepal, cover story headlines from nepal, current and latest cover story news from nepal, economic news from nepal, nepali cover story economic news and events, ongoing cover story news of nepal',

'description' => 'Multi-stakeholder Approach is the recent buzzword in development literature. How can Nepal use this approach? Achyut Wagle analyses the challenges and opportunities.',

'sortorder' => '587',

'feature_article' => true,

'user_id' => '0',

'image1' => null,

'image2' => null,

'image3' => null,

'image4' => null

),

'MagazineIssue' => array(

'id' => '472',

'image' => 'small_1389264715.jpg',

'sortorder' => '367',

'published' => true,

'created' => '2014-01-09 03:52:22',

'modified' => null,

'title' => 'Cover Story',

'publish_date' => '2014-01-01',

'parent_id' => '460',

'homepage' => false,

'user_id' => '0'

),

'MagazineCategory' => array(

'id' => null,

'title' => null,

'sortorder' => null,

'status' => null,

'created' => null,

'homepage' => null,

'modified' => null

),

'User' => array(

'password' => '*****',

'id' => null,

'user_detail_id' => null,

'group_id' => null,

'username' => null,

'name' => null,

'email' => null,

'address' => null,

'gender' => null,

'access' => null,

'phone' => null,

'access_type' => null,

'activated' => null,

'sortorder' => null,

'published' => null,

'created' => null,

'last_login' => null,

'ip' => null

),

'MagazineArticleComment' => array(),

'MagazineView' => array(

(int) 0 => array(

'magazine_article_id' => '613',

'hit' => '1550'

)

)

)

$current_user = null

$logged_in = false

$user = null

include - APP/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp, line 54

View::_evaluate() - CORE/Cake/View/View.php, line 971

View::_render() - CORE/Cake/View/View.php, line 933

View::render() - CORE/Cake/View/View.php, line 473

Controller::render() - CORE/Cake/Controller/Controller.php, line 968

Dispatcher::_invoke() - CORE/Cake/Routing/Dispatcher.php, line 200

Dispatcher::dispatch() - CORE/Cake/Routing/Dispatcher.php, line 167

[main] - APP/webroot/index.php, line 117

Notice (8): Trying to access array offset on value of type null [APP/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp, line 54]Code Context $user = $this->Session->read('Auth.User');

//find the group of logged user

$groupId = $user['Group']['id'];

$viewFile = '/var/www/html/newbusinessage.com/app/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp'

$dataForView = array(

'magazineArticle' => array(

'MagazineArticle' => array(

'id' => '613',

'magazine_issue_id' => '472',

'magazine_category_id' => '0',

'title' => 'Partners In Economic Growth',

'image' => null,

'short_content' => null,

'content' => '<div>

<img alt="Cover Story" src="/userfiles/images/CS%20(Copy).jpg" style="width: 550px; height: 540px; margin-left: 10px; margin-right: 10px;" /></div>

<div>