Notice (8): Trying to access array offset on value of type null [APP/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp, line 54]Code Context $user = $this->Session->read('Auth.User');

//find the group of logged user

$groupId = $user['Group']['id'];

$viewFile = '/var/www/html/newbusinessage.com/app/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp'

$dataForView = array(

'magazineArticle' => array(

'MagazineArticle' => array(

'id' => '1626',

'magazine_issue_id' => '967',

'magazine_category_id' => '103',

'title' => 'Nobel Signs the Contract',

'image' => null,

'short_content' => 'This year’s Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded jointly to economists Dr Oliver Simon D’Arcy Hart and Dr Bengt Holström for their contributions to the development of Contracts Theory. Dr Hart is a British-American who teaches Economics at Harvard',

'content' => '<p style="text-align: center;"><em><span style="font-size:16px">The key idea of the Contract Theory developed by both Nobel Laureates is that there is no such thing as a perfect contract.</span></em></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>--BY HOM NATH GAIRE</strong></p>

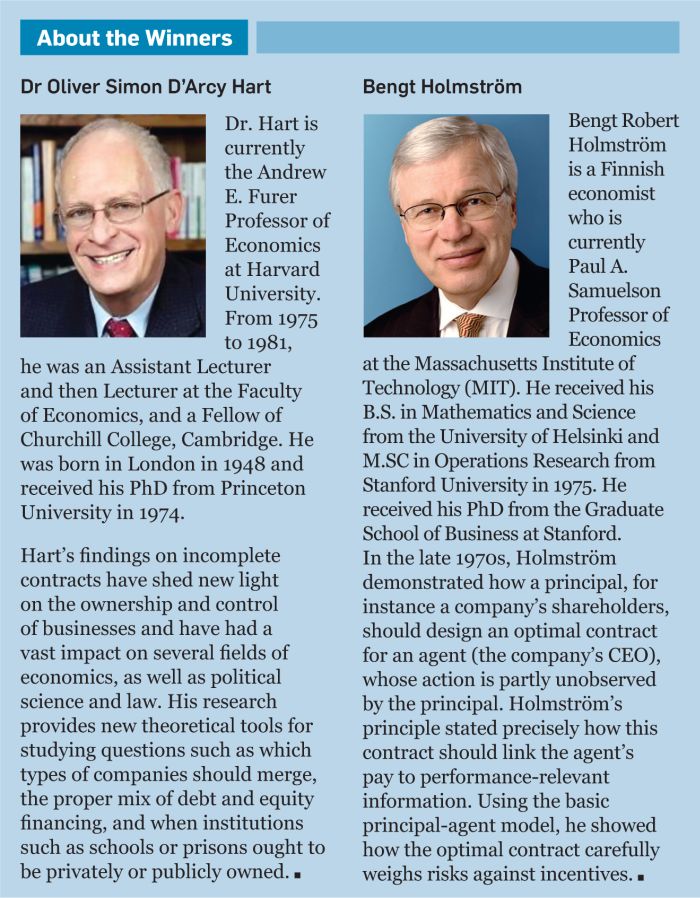

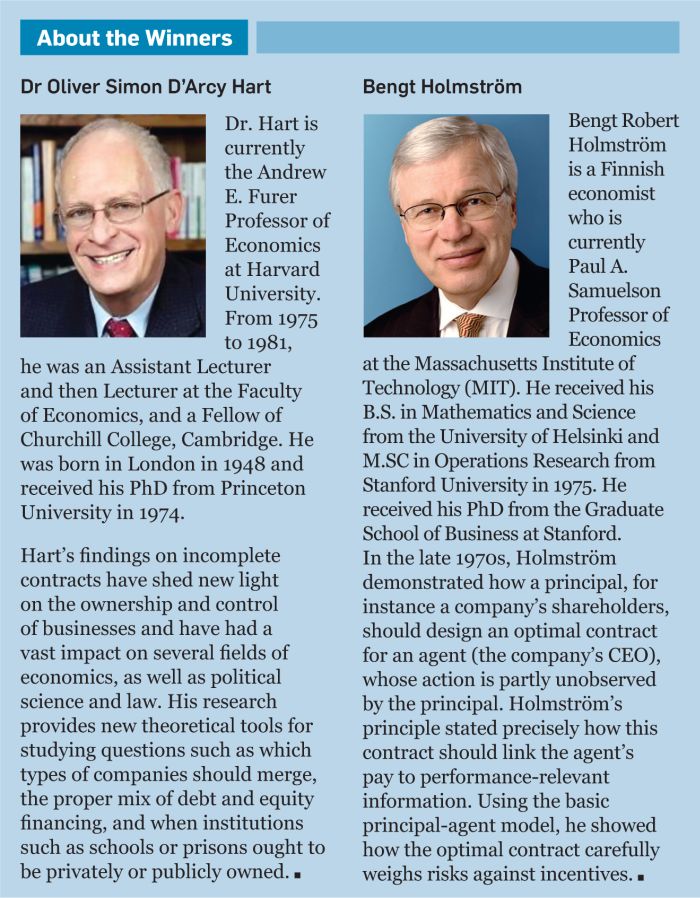

<p style="text-align: justify;">This year’s Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded jointly to economists Dr Oliver Simon D’Arcy Hart and Dr Bengt Holström for their contributions to the development of Contracts Theory. Dr Hart is a British-American who teaches Economics at Harvard and Dr Holström is Finnish who is a Professor of Economics at MIT. According to the Nobel Foundation, the prize was awarded for their compatible though not collaborative work on developing the theory of contracts into something more robust and informative.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Modern economies are operational and work together by innumerable contracts in one form or another. The theoretical tools, for which Hart and Holmström were awarded, are valuable for the practical understanding of real-life contracts and institutions, as well as potential pitfalls in the contract design.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">"This year’s Economics laureates have developed contract theory, a comprehensive framework for analyzing many diverse issues in contractual design, like performance-based pay for top executives, deductibles and co-pays in insurance, and the privatisation of public-sector activities," says the Nobel Foundation. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Many contractual relationships of modern society include associations between shareholders and top executive management, the rental company and house owners, and/or a public authority and its suppliers. As such relationships typically lead to conflicts of interest, contracts must be properly designed to ensure that the parties take mutually beneficial decisions. In this context, the key idea of the Contract Theory developed by both Nobel Laureates is that there is no such thing as a perfect contract. However, in some cases, it might be ideal to have a document that specifies every possible situation and every possible remedy complete with perfect and immediate information about exactly who did what and when. This is where Hart and Holmström worked independently and came out with the theories and principles, which tries to provide the tools to have the best possible contract. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size:16px"><strong>What is Contract? </strong></span><br />

Contract is a legally binding agreement that clarifies the responsibilities and obligations of all parties engaged in it in all circumstances. Irrespective of the types and areas, contracts are the lifeline of a functioning market economy. Everything from a credit card transaction to an employment agreement to deals with proprietors and suppliers and investments involves contracts. Without the contracts, no economic activity can exist- a crude form of barter market may be possible but not the vast sophistication of modern industrial and post-industrial activities.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">However, in the context of economic modeling, the contracts that constitute the binding ropes of the entire economy function like a magic box that simplify and reconcile the conflicting interests of the parties. Real contracts are, of course, nothing like that. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/nobel.jpg" style="height:898px; margin-left:10px; margin-right:10px; width:700px" /></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size:16px"><strong>Features of Contract Theory </strong></span><br />

Hart and Holmström developed the Contract Theory as a fertile field of applied research. Over the last few decades, they have also explored its various applications. Their analysis of optimal contractual arrangements lays an intellectual foundation for designing policies and institutions in many areas ranging from bankruptcy legislation to political constitutions. Below are some of the major features of Contracts Theory:</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>1. Government vs Private (who owns what)</strong><br />

Hart’s most interesting research centres on the ways where imperfections of contracts mean that it ultimately does matter who owns what. According to him, there is a meaningful difference between the government that operates a public utility and the government that contracts out the utility to a private operator. He has given an example of a prison, one that is directly managed by the government and another which is contracted out to a private operator. The private prison operator, unlike the government, has strong financial incentives to invest in new methods and processes for bringing down the costs. In this particular case, an incentive to cost reduction will lead to dismal outcomes. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">However, in other cases, contracting out management to incentivise reduction of costs can probably be a good idea. It would make perfect sense for the government to purchase the fighter jets from private aircraft manufacturers rather than to invest the money to manufacture such military hardware. These questions of where to draw the lines between public and private ownership are crucial for many policy issues. Hart’s research offers theoretical tools to help understand such questions.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">For instance, it also makes sense for a private company to own all elements of its supply chain rather than contracting with other companies for supplies. This is often treated as a pure question of financial engineering where the right answer is to own as little as possible to maximise the Return on Equity (ROI). Hart, however, argues that the entity that owns any underlying asset has an incentive to invest in its improvement, which further incentivizes it to own more assets. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>2. Principal-Agent Problem</strong><br />

It is hard to design the right rewards for managers and workers. In this regard, Holmström focuses on different aspects of the contracting relationship, which is one of the complicated interplays between owners, managers, and workers. It is considered to be desirable to “pay for performance,” thus encouraging people to perform their best. Here, Holmström’s main idea is that we cannot just financially reward people for outcomes. Rather we need to make sure the reward system is genuinely based on all the relevant information. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">The pay schemes of a CEO, for example, often fail to meet this standard. Both Nobel Laureates argue that CEOs are likely to be rewarded with bonuses when share prices rise even if the industry or the economy faces a slowdown. It means, managing a company during good times does not reflect the efficiency of a CEO. Conversely (though in practice this happens less often), blaming a CEO for being in charge during a stock market crash or economic recession makes very little sense.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>3. Incentives and Moral Hazard </strong><br />

The contract theory applies ideas about uncertainty to insurance contracts where, in practice, the insured party’s incentives are undermined by the existence of insurance. A paper by Holmström combines the ideas of insurance and compensation to provide a speculative account of why worker-owned companies have not been very successful. According to him, such owners do not get penalised for failures. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">This ends up rewarding the least diligent and least conscientious workers in the company. Here, separating ownership from work creates a group of dedicated punishers who ultimately drive superior performance.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>4. Informed Decision Making</strong><br />

An important aspect regarding the Nobel Prize to Hart and Holmström is there are more economic (micro) theories than very abstract economic (macro) models. Doing empirical studies on how contracts are written and enforced are more interesting and important, which helps to make informed decisions.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Nevertheless, it is difficult for people to make such decisions in real life. It would be utopian and unrealistic to assume that existing practices are optimal. Hart and Holmström use the tools of economic theory to investigate concrete, difficult problems in the design of market structures that rely on the informed decisions.</p>

<p style="text-align: right;"><em>The writer is Director of the Confederation of Nepalese Industries (CNI).</em></p>

',

'status' => true,

'publish_date' => '0000-00-00',

'created' => '2016-11-20 12:20:15',

'modified' => '2016-11-20 12:20:15',

'keywords' => '',

'description' => '',

'sortorder' => '1587',

'feature_article' => true,

'user_id' => '11',

'image1' => null,

'image2' => null,

'image3' => null,

'image4' => null

),

'MagazineIssue' => array(

'id' => '967',

'image' => '20161116023451_cover.JPG',

'sortorder' => '1516',

'published' => true,

'created' => '2016-11-16 14:34:51',

'modified' => '2016-11-16 14:53:11',

'title' => 'November 2016',

'publish_date' => '2016-11-01',

'parent_id' => '0',

'homepage' => true,

'user_id' => '11'

),

'MagazineCategory' => array(

'id' => '103',

'title' => 'Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences 2016',

'sortorder' => '103',

'status' => true,

'created' => '0000-00-00 00:00:00',

'homepage' => false,

'modified' => '2017-05-03 14:54:05'

),

'User' => array(

'password' => '*****',

'id' => '11',

'user_detail_id' => '0',

'group_id' => '24',

'username' => 'nsingha@abhiyan.com.np',

'name' => '',

'email' => 'nsingha@abhiyan.com.np',

'address' => '',

'gender' => '',

'access' => '1',

'phone' => '',

'access_type' => '0',

'activated' => false,

'sortorder' => '0',

'published' => '0',

'created' => '2015-04-08 13:22:59',

'last_login' => '2023-04-16 09:29:47',

'ip' => '172.69.77.43'

),

'MagazineArticleComment' => array(),

'MagazineView' => array(

(int) 0 => array(

[maximum depth reached]

)

)

),

'current_user' => null,

'logged_in' => false

)

$magazineArticle = array(

'MagazineArticle' => array(

'id' => '1626',

'magazine_issue_id' => '967',

'magazine_category_id' => '103',

'title' => 'Nobel Signs the Contract',

'image' => null,

'short_content' => 'This year’s Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded jointly to economists Dr Oliver Simon D’Arcy Hart and Dr Bengt Holström for their contributions to the development of Contracts Theory. Dr Hart is a British-American who teaches Economics at Harvard',

'content' => '<p style="text-align: center;"><em><span style="font-size:16px">The key idea of the Contract Theory developed by both Nobel Laureates is that there is no such thing as a perfect contract.</span></em></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>--BY HOM NATH GAIRE</strong></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">This year’s Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded jointly to economists Dr Oliver Simon D’Arcy Hart and Dr Bengt Holström for their contributions to the development of Contracts Theory. Dr Hart is a British-American who teaches Economics at Harvard and Dr Holström is Finnish who is a Professor of Economics at MIT. According to the Nobel Foundation, the prize was awarded for their compatible though not collaborative work on developing the theory of contracts into something more robust and informative.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Modern economies are operational and work together by innumerable contracts in one form or another. The theoretical tools, for which Hart and Holmström were awarded, are valuable for the practical understanding of real-life contracts and institutions, as well as potential pitfalls in the contract design.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">"This year’s Economics laureates have developed contract theory, a comprehensive framework for analyzing many diverse issues in contractual design, like performance-based pay for top executives, deductibles and co-pays in insurance, and the privatisation of public-sector activities," says the Nobel Foundation. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Many contractual relationships of modern society include associations between shareholders and top executive management, the rental company and house owners, and/or a public authority and its suppliers. As such relationships typically lead to conflicts of interest, contracts must be properly designed to ensure that the parties take mutually beneficial decisions. In this context, the key idea of the Contract Theory developed by both Nobel Laureates is that there is no such thing as a perfect contract. However, in some cases, it might be ideal to have a document that specifies every possible situation and every possible remedy complete with perfect and immediate information about exactly who did what and when. This is where Hart and Holmström worked independently and came out with the theories and principles, which tries to provide the tools to have the best possible contract. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size:16px"><strong>What is Contract? </strong></span><br />

Contract is a legally binding agreement that clarifies the responsibilities and obligations of all parties engaged in it in all circumstances. Irrespective of the types and areas, contracts are the lifeline of a functioning market economy. Everything from a credit card transaction to an employment agreement to deals with proprietors and suppliers and investments involves contracts. Without the contracts, no economic activity can exist- a crude form of barter market may be possible but not the vast sophistication of modern industrial and post-industrial activities.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">However, in the context of economic modeling, the contracts that constitute the binding ropes of the entire economy function like a magic box that simplify and reconcile the conflicting interests of the parties. Real contracts are, of course, nothing like that. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/nobel.jpg" style="height:898px; margin-left:10px; margin-right:10px; width:700px" /></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size:16px"><strong>Features of Contract Theory </strong></span><br />

Hart and Holmström developed the Contract Theory as a fertile field of applied research. Over the last few decades, they have also explored its various applications. Their analysis of optimal contractual arrangements lays an intellectual foundation for designing policies and institutions in many areas ranging from bankruptcy legislation to political constitutions. Below are some of the major features of Contracts Theory:</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>1. Government vs Private (who owns what)</strong><br />

Hart’s most interesting research centres on the ways where imperfections of contracts mean that it ultimately does matter who owns what. According to him, there is a meaningful difference between the government that operates a public utility and the government that contracts out the utility to a private operator. He has given an example of a prison, one that is directly managed by the government and another which is contracted out to a private operator. The private prison operator, unlike the government, has strong financial incentives to invest in new methods and processes for bringing down the costs. In this particular case, an incentive to cost reduction will lead to dismal outcomes. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">However, in other cases, contracting out management to incentivise reduction of costs can probably be a good idea. It would make perfect sense for the government to purchase the fighter jets from private aircraft manufacturers rather than to invest the money to manufacture such military hardware. These questions of where to draw the lines between public and private ownership are crucial for many policy issues. Hart’s research offers theoretical tools to help understand such questions.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">For instance, it also makes sense for a private company to own all elements of its supply chain rather than contracting with other companies for supplies. This is often treated as a pure question of financial engineering where the right answer is to own as little as possible to maximise the Return on Equity (ROI). Hart, however, argues that the entity that owns any underlying asset has an incentive to invest in its improvement, which further incentivizes it to own more assets. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>2. Principal-Agent Problem</strong><br />

It is hard to design the right rewards for managers and workers. In this regard, Holmström focuses on different aspects of the contracting relationship, which is one of the complicated interplays between owners, managers, and workers. It is considered to be desirable to “pay for performance,” thus encouraging people to perform their best. Here, Holmström’s main idea is that we cannot just financially reward people for outcomes. Rather we need to make sure the reward system is genuinely based on all the relevant information. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">The pay schemes of a CEO, for example, often fail to meet this standard. Both Nobel Laureates argue that CEOs are likely to be rewarded with bonuses when share prices rise even if the industry or the economy faces a slowdown. It means, managing a company during good times does not reflect the efficiency of a CEO. Conversely (though in practice this happens less often), blaming a CEO for being in charge during a stock market crash or economic recession makes very little sense.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>3. Incentives and Moral Hazard </strong><br />

The contract theory applies ideas about uncertainty to insurance contracts where, in practice, the insured party’s incentives are undermined by the existence of insurance. A paper by Holmström combines the ideas of insurance and compensation to provide a speculative account of why worker-owned companies have not been very successful. According to him, such owners do not get penalised for failures. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">This ends up rewarding the least diligent and least conscientious workers in the company. Here, separating ownership from work creates a group of dedicated punishers who ultimately drive superior performance.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>4. Informed Decision Making</strong><br />

An important aspect regarding the Nobel Prize to Hart and Holmström is there are more economic (micro) theories than very abstract economic (macro) models. Doing empirical studies on how contracts are written and enforced are more interesting and important, which helps to make informed decisions.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Nevertheless, it is difficult for people to make such decisions in real life. It would be utopian and unrealistic to assume that existing practices are optimal. Hart and Holmström use the tools of economic theory to investigate concrete, difficult problems in the design of market structures that rely on the informed decisions.</p>

<p style="text-align: right;"><em>The writer is Director of the Confederation of Nepalese Industries (CNI).</em></p>

',

'status' => true,

'publish_date' => '0000-00-00',

'created' => '2016-11-20 12:20:15',

'modified' => '2016-11-20 12:20:15',

'keywords' => '',

'description' => '',

'sortorder' => '1587',

'feature_article' => true,

'user_id' => '11',

'image1' => null,

'image2' => null,

'image3' => null,

'image4' => null

),

'MagazineIssue' => array(

'id' => '967',

'image' => '20161116023451_cover.JPG',

'sortorder' => '1516',

'published' => true,

'created' => '2016-11-16 14:34:51',

'modified' => '2016-11-16 14:53:11',

'title' => 'November 2016',

'publish_date' => '2016-11-01',

'parent_id' => '0',

'homepage' => true,

'user_id' => '11'

),

'MagazineCategory' => array(

'id' => '103',

'title' => 'Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences 2016',

'sortorder' => '103',

'status' => true,

'created' => '0000-00-00 00:00:00',

'homepage' => false,

'modified' => '2017-05-03 14:54:05'

),

'User' => array(

'password' => '*****',

'id' => '11',

'user_detail_id' => '0',

'group_id' => '24',

'username' => 'nsingha@abhiyan.com.np',

'name' => '',

'email' => 'nsingha@abhiyan.com.np',

'address' => '',

'gender' => '',

'access' => '1',

'phone' => '',

'access_type' => '0',

'activated' => false,

'sortorder' => '0',

'published' => '0',

'created' => '2015-04-08 13:22:59',

'last_login' => '2023-04-16 09:29:47',

'ip' => '172.69.77.43'

),

'MagazineArticleComment' => array(),

'MagazineView' => array(

(int) 0 => array(

'magazine_article_id' => '1626',

'hit' => '3504'

)

)

)

$current_user = null

$logged_in = false

$user = null

include - APP/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp, line 54

View::_evaluate() - CORE/Cake/View/View.php, line 971

View::_render() - CORE/Cake/View/View.php, line 933

View::render() - CORE/Cake/View/View.php, line 473

Controller::render() - CORE/Cake/Controller/Controller.php, line 968

Dispatcher::_invoke() - CORE/Cake/Routing/Dispatcher.php, line 200

Dispatcher::dispatch() - CORE/Cake/Routing/Dispatcher.php, line 167

[main] - APP/webroot/index.php, line 117

Notice (8): Trying to access array offset on value of type null [APP/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp, line 54]Code Context $user = $this->Session->read('Auth.User');

//find the group of logged user

$groupId = $user['Group']['id'];

$viewFile = '/var/www/html/newbusinessage.com/app/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp'

$dataForView = array(

'magazineArticle' => array(

'MagazineArticle' => array(

'id' => '1626',

'magazine_issue_id' => '967',

'magazine_category_id' => '103',

'title' => 'Nobel Signs the Contract',

'image' => null,

'short_content' => 'This year’s Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded jointly to economists Dr Oliver Simon D’Arcy Hart and Dr Bengt Holström for their contributions to the development of Contracts Theory. Dr Hart is a British-American who teaches Economics at Harvard',

'content' => '<p style="text-align: center;"><em><span style="font-size:16px">The key idea of the Contract Theory developed by both Nobel Laureates is that there is no such thing as a perfect contract.</span></em></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>--BY HOM NATH GAIRE</strong></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">This year’s Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded jointly to economists Dr Oliver Simon D’Arcy Hart and Dr Bengt Holström for their contributions to the development of Contracts Theory. Dr Hart is a British-American who teaches Economics at Harvard and Dr Holström is Finnish who is a Professor of Economics at MIT. According to the Nobel Foundation, the prize was awarded for their compatible though not collaborative work on developing the theory of contracts into something more robust and informative.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Modern economies are operational and work together by innumerable contracts in one form or another. The theoretical tools, for which Hart and Holmström were awarded, are valuable for the practical understanding of real-life contracts and institutions, as well as potential pitfalls in the contract design.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">"This year’s Economics laureates have developed contract theory, a comprehensive framework for analyzing many diverse issues in contractual design, like performance-based pay for top executives, deductibles and co-pays in insurance, and the privatisation of public-sector activities," says the Nobel Foundation. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Many contractual relationships of modern society include associations between shareholders and top executive management, the rental company and house owners, and/or a public authority and its suppliers. As such relationships typically lead to conflicts of interest, contracts must be properly designed to ensure that the parties take mutually beneficial decisions. In this context, the key idea of the Contract Theory developed by both Nobel Laureates is that there is no such thing as a perfect contract. However, in some cases, it might be ideal to have a document that specifies every possible situation and every possible remedy complete with perfect and immediate information about exactly who did what and when. This is where Hart and Holmström worked independently and came out with the theories and principles, which tries to provide the tools to have the best possible contract. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size:16px"><strong>What is Contract? </strong></span><br />

Contract is a legally binding agreement that clarifies the responsibilities and obligations of all parties engaged in it in all circumstances. Irrespective of the types and areas, contracts are the lifeline of a functioning market economy. Everything from a credit card transaction to an employment agreement to deals with proprietors and suppliers and investments involves contracts. Without the contracts, no economic activity can exist- a crude form of barter market may be possible but not the vast sophistication of modern industrial and post-industrial activities.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">However, in the context of economic modeling, the contracts that constitute the binding ropes of the entire economy function like a magic box that simplify and reconcile the conflicting interests of the parties. Real contracts are, of course, nothing like that. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/nobel.jpg" style="height:898px; margin-left:10px; margin-right:10px; width:700px" /></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size:16px"><strong>Features of Contract Theory </strong></span><br />

Hart and Holmström developed the Contract Theory as a fertile field of applied research. Over the last few decades, they have also explored its various applications. Their analysis of optimal contractual arrangements lays an intellectual foundation for designing policies and institutions in many areas ranging from bankruptcy legislation to political constitutions. Below are some of the major features of Contracts Theory:</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>1. Government vs Private (who owns what)</strong><br />

Hart’s most interesting research centres on the ways where imperfections of contracts mean that it ultimately does matter who owns what. According to him, there is a meaningful difference between the government that operates a public utility and the government that contracts out the utility to a private operator. He has given an example of a prison, one that is directly managed by the government and another which is contracted out to a private operator. The private prison operator, unlike the government, has strong financial incentives to invest in new methods and processes for bringing down the costs. In this particular case, an incentive to cost reduction will lead to dismal outcomes. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">However, in other cases, contracting out management to incentivise reduction of costs can probably be a good idea. It would make perfect sense for the government to purchase the fighter jets from private aircraft manufacturers rather than to invest the money to manufacture such military hardware. These questions of where to draw the lines between public and private ownership are crucial for many policy issues. Hart’s research offers theoretical tools to help understand such questions.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">For instance, it also makes sense for a private company to own all elements of its supply chain rather than contracting with other companies for supplies. This is often treated as a pure question of financial engineering where the right answer is to own as little as possible to maximise the Return on Equity (ROI). Hart, however, argues that the entity that owns any underlying asset has an incentive to invest in its improvement, which further incentivizes it to own more assets. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>2. Principal-Agent Problem</strong><br />

It is hard to design the right rewards for managers and workers. In this regard, Holmström focuses on different aspects of the contracting relationship, which is one of the complicated interplays between owners, managers, and workers. It is considered to be desirable to “pay for performance,” thus encouraging people to perform their best. Here, Holmström’s main idea is that we cannot just financially reward people for outcomes. Rather we need to make sure the reward system is genuinely based on all the relevant information. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">The pay schemes of a CEO, for example, often fail to meet this standard. Both Nobel Laureates argue that CEOs are likely to be rewarded with bonuses when share prices rise even if the industry or the economy faces a slowdown. It means, managing a company during good times does not reflect the efficiency of a CEO. Conversely (though in practice this happens less often), blaming a CEO for being in charge during a stock market crash or economic recession makes very little sense.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>3. Incentives and Moral Hazard </strong><br />

The contract theory applies ideas about uncertainty to insurance contracts where, in practice, the insured party’s incentives are undermined by the existence of insurance. A paper by Holmström combines the ideas of insurance and compensation to provide a speculative account of why worker-owned companies have not been very successful. According to him, such owners do not get penalised for failures. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">This ends up rewarding the least diligent and least conscientious workers in the company. Here, separating ownership from work creates a group of dedicated punishers who ultimately drive superior performance.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>4. Informed Decision Making</strong><br />

An important aspect regarding the Nobel Prize to Hart and Holmström is there are more economic (micro) theories than very abstract economic (macro) models. Doing empirical studies on how contracts are written and enforced are more interesting and important, which helps to make informed decisions.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Nevertheless, it is difficult for people to make such decisions in real life. It would be utopian and unrealistic to assume that existing practices are optimal. Hart and Holmström use the tools of economic theory to investigate concrete, difficult problems in the design of market structures that rely on the informed decisions.</p>

<p style="text-align: right;"><em>The writer is Director of the Confederation of Nepalese Industries (CNI).</em></p>

',

'status' => true,

'publish_date' => '0000-00-00',

'created' => '2016-11-20 12:20:15',

'modified' => '2016-11-20 12:20:15',

'keywords' => '',

'description' => '',

'sortorder' => '1587',

'feature_article' => true,

'user_id' => '11',

'image1' => null,

'image2' => null,

'image3' => null,

'image4' => null

),

'MagazineIssue' => array(

'id' => '967',

'image' => '20161116023451_cover.JPG',

'sortorder' => '1516',

'published' => true,

'created' => '2016-11-16 14:34:51',

'modified' => '2016-11-16 14:53:11',

'title' => 'November 2016',

'publish_date' => '2016-11-01',

'parent_id' => '0',

'homepage' => true,

'user_id' => '11'

),

'MagazineCategory' => array(

'id' => '103',

'title' => 'Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences 2016',

'sortorder' => '103',

'status' => true,

'created' => '0000-00-00 00:00:00',

'homepage' => false,

'modified' => '2017-05-03 14:54:05'

),

'User' => array(

'password' => '*****',

'id' => '11',

'user_detail_id' => '0',

'group_id' => '24',

'username' => 'nsingha@abhiyan.com.np',

'name' => '',

'email' => 'nsingha@abhiyan.com.np',

'address' => '',

'gender' => '',

'access' => '1',

'phone' => '',

'access_type' => '0',

'activated' => false,

'sortorder' => '0',

'published' => '0',

'created' => '2015-04-08 13:22:59',

'last_login' => '2023-04-16 09:29:47',

'ip' => '172.69.77.43'

),

'MagazineArticleComment' => array(),

'MagazineView' => array(

(int) 0 => array(

[maximum depth reached]

)

)

),

'current_user' => null,

'logged_in' => false

)

$magazineArticle = array(

'MagazineArticle' => array(

'id' => '1626',

'magazine_issue_id' => '967',

'magazine_category_id' => '103',

'title' => 'Nobel Signs the Contract',

'image' => null,

'short_content' => 'This year’s Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded jointly to economists Dr Oliver Simon D’Arcy Hart and Dr Bengt Holström for their contributions to the development of Contracts Theory. Dr Hart is a British-American who teaches Economics at Harvard',

'content' => '<p style="text-align: center;"><em><span style="font-size:16px">The key idea of the Contract Theory developed by both Nobel Laureates is that there is no such thing as a perfect contract.</span></em></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>--BY HOM NATH GAIRE</strong></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">This year’s Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded jointly to economists Dr Oliver Simon D’Arcy Hart and Dr Bengt Holström for their contributions to the development of Contracts Theory. Dr Hart is a British-American who teaches Economics at Harvard and Dr Holström is Finnish who is a Professor of Economics at MIT. According to the Nobel Foundation, the prize was awarded for their compatible though not collaborative work on developing the theory of contracts into something more robust and informative.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Modern economies are operational and work together by innumerable contracts in one form or another. The theoretical tools, for which Hart and Holmström were awarded, are valuable for the practical understanding of real-life contracts and institutions, as well as potential pitfalls in the contract design.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">"This year’s Economics laureates have developed contract theory, a comprehensive framework for analyzing many diverse issues in contractual design, like performance-based pay for top executives, deductibles and co-pays in insurance, and the privatisation of public-sector activities," says the Nobel Foundation. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Many contractual relationships of modern society include associations between shareholders and top executive management, the rental company and house owners, and/or a public authority and its suppliers. As such relationships typically lead to conflicts of interest, contracts must be properly designed to ensure that the parties take mutually beneficial decisions. In this context, the key idea of the Contract Theory developed by both Nobel Laureates is that there is no such thing as a perfect contract. However, in some cases, it might be ideal to have a document that specifies every possible situation and every possible remedy complete with perfect and immediate information about exactly who did what and when. This is where Hart and Holmström worked independently and came out with the theories and principles, which tries to provide the tools to have the best possible contract. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size:16px"><strong>What is Contract? </strong></span><br />

Contract is a legally binding agreement that clarifies the responsibilities and obligations of all parties engaged in it in all circumstances. Irrespective of the types and areas, contracts are the lifeline of a functioning market economy. Everything from a credit card transaction to an employment agreement to deals with proprietors and suppliers and investments involves contracts. Without the contracts, no economic activity can exist- a crude form of barter market may be possible but not the vast sophistication of modern industrial and post-industrial activities.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">However, in the context of economic modeling, the contracts that constitute the binding ropes of the entire economy function like a magic box that simplify and reconcile the conflicting interests of the parties. Real contracts are, of course, nothing like that. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/nobel.jpg" style="height:898px; margin-left:10px; margin-right:10px; width:700px" /></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size:16px"><strong>Features of Contract Theory </strong></span><br />

Hart and Holmström developed the Contract Theory as a fertile field of applied research. Over the last few decades, they have also explored its various applications. Their analysis of optimal contractual arrangements lays an intellectual foundation for designing policies and institutions in many areas ranging from bankruptcy legislation to political constitutions. Below are some of the major features of Contracts Theory:</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>1. Government vs Private (who owns what)</strong><br />

Hart’s most interesting research centres on the ways where imperfections of contracts mean that it ultimately does matter who owns what. According to him, there is a meaningful difference between the government that operates a public utility and the government that contracts out the utility to a private operator. He has given an example of a prison, one that is directly managed by the government and another which is contracted out to a private operator. The private prison operator, unlike the government, has strong financial incentives to invest in new methods and processes for bringing down the costs. In this particular case, an incentive to cost reduction will lead to dismal outcomes. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">However, in other cases, contracting out management to incentivise reduction of costs can probably be a good idea. It would make perfect sense for the government to purchase the fighter jets from private aircraft manufacturers rather than to invest the money to manufacture such military hardware. These questions of where to draw the lines between public and private ownership are crucial for many policy issues. Hart’s research offers theoretical tools to help understand such questions.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">For instance, it also makes sense for a private company to own all elements of its supply chain rather than contracting with other companies for supplies. This is often treated as a pure question of financial engineering where the right answer is to own as little as possible to maximise the Return on Equity (ROI). Hart, however, argues that the entity that owns any underlying asset has an incentive to invest in its improvement, which further incentivizes it to own more assets. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>2. Principal-Agent Problem</strong><br />

It is hard to design the right rewards for managers and workers. In this regard, Holmström focuses on different aspects of the contracting relationship, which is one of the complicated interplays between owners, managers, and workers. It is considered to be desirable to “pay for performance,” thus encouraging people to perform their best. Here, Holmström’s main idea is that we cannot just financially reward people for outcomes. Rather we need to make sure the reward system is genuinely based on all the relevant information. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">The pay schemes of a CEO, for example, often fail to meet this standard. Both Nobel Laureates argue that CEOs are likely to be rewarded with bonuses when share prices rise even if the industry or the economy faces a slowdown. It means, managing a company during good times does not reflect the efficiency of a CEO. Conversely (though in practice this happens less often), blaming a CEO for being in charge during a stock market crash or economic recession makes very little sense.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>3. Incentives and Moral Hazard </strong><br />

The contract theory applies ideas about uncertainty to insurance contracts where, in practice, the insured party’s incentives are undermined by the existence of insurance. A paper by Holmström combines the ideas of insurance and compensation to provide a speculative account of why worker-owned companies have not been very successful. According to him, such owners do not get penalised for failures. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">This ends up rewarding the least diligent and least conscientious workers in the company. Here, separating ownership from work creates a group of dedicated punishers who ultimately drive superior performance.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>4. Informed Decision Making</strong><br />

An important aspect regarding the Nobel Prize to Hart and Holmström is there are more economic (micro) theories than very abstract economic (macro) models. Doing empirical studies on how contracts are written and enforced are more interesting and important, which helps to make informed decisions.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Nevertheless, it is difficult for people to make such decisions in real life. It would be utopian and unrealistic to assume that existing practices are optimal. Hart and Holmström use the tools of economic theory to investigate concrete, difficult problems in the design of market structures that rely on the informed decisions.</p>

<p style="text-align: right;"><em>The writer is Director of the Confederation of Nepalese Industries (CNI).</em></p>

',

'status' => true,

'publish_date' => '0000-00-00',

'created' => '2016-11-20 12:20:15',

'modified' => '2016-11-20 12:20:15',

'keywords' => '',

'description' => '',

'sortorder' => '1587',

'feature_article' => true,

'user_id' => '11',

'image1' => null,

'image2' => null,

'image3' => null,

'image4' => null

),

'MagazineIssue' => array(

'id' => '967',

'image' => '20161116023451_cover.JPG',

'sortorder' => '1516',

'published' => true,

'created' => '2016-11-16 14:34:51',

'modified' => '2016-11-16 14:53:11',

'title' => 'November 2016',

'publish_date' => '2016-11-01',

'parent_id' => '0',

'homepage' => true,

'user_id' => '11'

),

'MagazineCategory' => array(

'id' => '103',

'title' => 'Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences 2016',

'sortorder' => '103',

'status' => true,

'created' => '0000-00-00 00:00:00',

'homepage' => false,

'modified' => '2017-05-03 14:54:05'

),

'User' => array(

'password' => '*****',

'id' => '11',

'user_detail_id' => '0',

'group_id' => '24',

'username' => 'nsingha@abhiyan.com.np',

'name' => '',

'email' => 'nsingha@abhiyan.com.np',

'address' => '',

'gender' => '',

'access' => '1',

'phone' => '',

'access_type' => '0',

'activated' => false,

'sortorder' => '0',

'published' => '0',

'created' => '2015-04-08 13:22:59',

'last_login' => '2023-04-16 09:29:47',

'ip' => '172.69.77.43'

),

'MagazineArticleComment' => array(),

'MagazineView' => array(

(int) 0 => array(

'magazine_article_id' => '1626',

'hit' => '3504'

)

)

)

$current_user = null

$logged_in = false

$user = null

include - APP/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp, line 54

View::_evaluate() - CORE/Cake/View/View.php, line 971

View::_render() - CORE/Cake/View/View.php, line 933

View::render() - CORE/Cake/View/View.php, line 473

Controller::render() - CORE/Cake/Controller/Controller.php, line 968

Dispatcher::_invoke() - CORE/Cake/Routing/Dispatcher.php, line 200

Dispatcher::dispatch() - CORE/Cake/Routing/Dispatcher.php, line 167

[main] - APP/webroot/index.php, line 117

Notice (8): Trying to access array offset on value of type null [APP/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp, line 55]Code Context //find the group of logged user

$groupId = $user['Group']['id'];

$user_id=$user["id"];

$viewFile = '/var/www/html/newbusinessage.com/app/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp'

$dataForView = array(

'magazineArticle' => array(

'MagazineArticle' => array(

'id' => '1626',

'magazine_issue_id' => '967',

'magazine_category_id' => '103',

'title' => 'Nobel Signs the Contract',

'image' => null,

'short_content' => 'This year’s Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded jointly to economists Dr Oliver Simon D’Arcy Hart and Dr Bengt Holström for their contributions to the development of Contracts Theory. Dr Hart is a British-American who teaches Economics at Harvard',

'content' => '<p style="text-align: center;"><em><span style="font-size:16px">The key idea of the Contract Theory developed by both Nobel Laureates is that there is no such thing as a perfect contract.</span></em></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>--BY HOM NATH GAIRE</strong></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">This year’s Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded jointly to economists Dr Oliver Simon D’Arcy Hart and Dr Bengt Holström for their contributions to the development of Contracts Theory. Dr Hart is a British-American who teaches Economics at Harvard and Dr Holström is Finnish who is a Professor of Economics at MIT. According to the Nobel Foundation, the prize was awarded for their compatible though not collaborative work on developing the theory of contracts into something more robust and informative.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Modern economies are operational and work together by innumerable contracts in one form or another. The theoretical tools, for which Hart and Holmström were awarded, are valuable for the practical understanding of real-life contracts and institutions, as well as potential pitfalls in the contract design.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">"This year’s Economics laureates have developed contract theory, a comprehensive framework for analyzing many diverse issues in contractual design, like performance-based pay for top executives, deductibles and co-pays in insurance, and the privatisation of public-sector activities," says the Nobel Foundation. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Many contractual relationships of modern society include associations between shareholders and top executive management, the rental company and house owners, and/or a public authority and its suppliers. As such relationships typically lead to conflicts of interest, contracts must be properly designed to ensure that the parties take mutually beneficial decisions. In this context, the key idea of the Contract Theory developed by both Nobel Laureates is that there is no such thing as a perfect contract. However, in some cases, it might be ideal to have a document that specifies every possible situation and every possible remedy complete with perfect and immediate information about exactly who did what and when. This is where Hart and Holmström worked independently and came out with the theories and principles, which tries to provide the tools to have the best possible contract. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size:16px"><strong>What is Contract? </strong></span><br />

Contract is a legally binding agreement that clarifies the responsibilities and obligations of all parties engaged in it in all circumstances. Irrespective of the types and areas, contracts are the lifeline of a functioning market economy. Everything from a credit card transaction to an employment agreement to deals with proprietors and suppliers and investments involves contracts. Without the contracts, no economic activity can exist- a crude form of barter market may be possible but not the vast sophistication of modern industrial and post-industrial activities.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">However, in the context of economic modeling, the contracts that constitute the binding ropes of the entire economy function like a magic box that simplify and reconcile the conflicting interests of the parties. Real contracts are, of course, nothing like that. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/nobel.jpg" style="height:898px; margin-left:10px; margin-right:10px; width:700px" /></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size:16px"><strong>Features of Contract Theory </strong></span><br />

Hart and Holmström developed the Contract Theory as a fertile field of applied research. Over the last few decades, they have also explored its various applications. Their analysis of optimal contractual arrangements lays an intellectual foundation for designing policies and institutions in many areas ranging from bankruptcy legislation to political constitutions. Below are some of the major features of Contracts Theory:</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>1. Government vs Private (who owns what)</strong><br />

Hart’s most interesting research centres on the ways where imperfections of contracts mean that it ultimately does matter who owns what. According to him, there is a meaningful difference between the government that operates a public utility and the government that contracts out the utility to a private operator. He has given an example of a prison, one that is directly managed by the government and another which is contracted out to a private operator. The private prison operator, unlike the government, has strong financial incentives to invest in new methods and processes for bringing down the costs. In this particular case, an incentive to cost reduction will lead to dismal outcomes. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">However, in other cases, contracting out management to incentivise reduction of costs can probably be a good idea. It would make perfect sense for the government to purchase the fighter jets from private aircraft manufacturers rather than to invest the money to manufacture such military hardware. These questions of where to draw the lines between public and private ownership are crucial for many policy issues. Hart’s research offers theoretical tools to help understand such questions.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">For instance, it also makes sense for a private company to own all elements of its supply chain rather than contracting with other companies for supplies. This is often treated as a pure question of financial engineering where the right answer is to own as little as possible to maximise the Return on Equity (ROI). Hart, however, argues that the entity that owns any underlying asset has an incentive to invest in its improvement, which further incentivizes it to own more assets. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>2. Principal-Agent Problem</strong><br />

It is hard to design the right rewards for managers and workers. In this regard, Holmström focuses on different aspects of the contracting relationship, which is one of the complicated interplays between owners, managers, and workers. It is considered to be desirable to “pay for performance,” thus encouraging people to perform their best. Here, Holmström’s main idea is that we cannot just financially reward people for outcomes. Rather we need to make sure the reward system is genuinely based on all the relevant information. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">The pay schemes of a CEO, for example, often fail to meet this standard. Both Nobel Laureates argue that CEOs are likely to be rewarded with bonuses when share prices rise even if the industry or the economy faces a slowdown. It means, managing a company during good times does not reflect the efficiency of a CEO. Conversely (though in practice this happens less often), blaming a CEO for being in charge during a stock market crash or economic recession makes very little sense.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>3. Incentives and Moral Hazard </strong><br />

The contract theory applies ideas about uncertainty to insurance contracts where, in practice, the insured party’s incentives are undermined by the existence of insurance. A paper by Holmström combines the ideas of insurance and compensation to provide a speculative account of why worker-owned companies have not been very successful. According to him, such owners do not get penalised for failures. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">This ends up rewarding the least diligent and least conscientious workers in the company. Here, separating ownership from work creates a group of dedicated punishers who ultimately drive superior performance.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>4. Informed Decision Making</strong><br />

An important aspect regarding the Nobel Prize to Hart and Holmström is there are more economic (micro) theories than very abstract economic (macro) models. Doing empirical studies on how contracts are written and enforced are more interesting and important, which helps to make informed decisions.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Nevertheless, it is difficult for people to make such decisions in real life. It would be utopian and unrealistic to assume that existing practices are optimal. Hart and Holmström use the tools of economic theory to investigate concrete, difficult problems in the design of market structures that rely on the informed decisions.</p>

<p style="text-align: right;"><em>The writer is Director of the Confederation of Nepalese Industries (CNI).</em></p>

',

'status' => true,

'publish_date' => '0000-00-00',

'created' => '2016-11-20 12:20:15',

'modified' => '2016-11-20 12:20:15',

'keywords' => '',

'description' => '',

'sortorder' => '1587',

'feature_article' => true,

'user_id' => '11',

'image1' => null,

'image2' => null,

'image3' => null,

'image4' => null

),

'MagazineIssue' => array(

'id' => '967',

'image' => '20161116023451_cover.JPG',

'sortorder' => '1516',

'published' => true,

'created' => '2016-11-16 14:34:51',

'modified' => '2016-11-16 14:53:11',

'title' => 'November 2016',

'publish_date' => '2016-11-01',

'parent_id' => '0',

'homepage' => true,

'user_id' => '11'

),

'MagazineCategory' => array(

'id' => '103',

'title' => 'Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences 2016',

'sortorder' => '103',

'status' => true,

'created' => '0000-00-00 00:00:00',

'homepage' => false,

'modified' => '2017-05-03 14:54:05'

),

'User' => array(

'password' => '*****',

'id' => '11',

'user_detail_id' => '0',

'group_id' => '24',

'username' => 'nsingha@abhiyan.com.np',

'name' => '',

'email' => 'nsingha@abhiyan.com.np',

'address' => '',

'gender' => '',

'access' => '1',

'phone' => '',

'access_type' => '0',

'activated' => false,

'sortorder' => '0',

'published' => '0',

'created' => '2015-04-08 13:22:59',

'last_login' => '2023-04-16 09:29:47',

'ip' => '172.69.77.43'

),

'MagazineArticleComment' => array(),

'MagazineView' => array(

(int) 0 => array(

[maximum depth reached]

)

)

),

'current_user' => null,

'logged_in' => false

)

$magazineArticle = array(

'MagazineArticle' => array(

'id' => '1626',

'magazine_issue_id' => '967',

'magazine_category_id' => '103',

'title' => 'Nobel Signs the Contract',

'image' => null,

'short_content' => 'This year’s Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded jointly to economists Dr Oliver Simon D’Arcy Hart and Dr Bengt Holström for their contributions to the development of Contracts Theory. Dr Hart is a British-American who teaches Economics at Harvard',

'content' => '<p style="text-align: center;"><em><span style="font-size:16px">The key idea of the Contract Theory developed by both Nobel Laureates is that there is no such thing as a perfect contract.</span></em></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>--BY HOM NATH GAIRE</strong></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">This year’s Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded jointly to economists Dr Oliver Simon D’Arcy Hart and Dr Bengt Holström for their contributions to the development of Contracts Theory. Dr Hart is a British-American who teaches Economics at Harvard and Dr Holström is Finnish who is a Professor of Economics at MIT. According to the Nobel Foundation, the prize was awarded for their compatible though not collaborative work on developing the theory of contracts into something more robust and informative.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Modern economies are operational and work together by innumerable contracts in one form or another. The theoretical tools, for which Hart and Holmström were awarded, are valuable for the practical understanding of real-life contracts and institutions, as well as potential pitfalls in the contract design.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">"This year’s Economics laureates have developed contract theory, a comprehensive framework for analyzing many diverse issues in contractual design, like performance-based pay for top executives, deductibles and co-pays in insurance, and the privatisation of public-sector activities," says the Nobel Foundation. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Many contractual relationships of modern society include associations between shareholders and top executive management, the rental company and house owners, and/or a public authority and its suppliers. As such relationships typically lead to conflicts of interest, contracts must be properly designed to ensure that the parties take mutually beneficial decisions. In this context, the key idea of the Contract Theory developed by both Nobel Laureates is that there is no such thing as a perfect contract. However, in some cases, it might be ideal to have a document that specifies every possible situation and every possible remedy complete with perfect and immediate information about exactly who did what and when. This is where Hart and Holmström worked independently and came out with the theories and principles, which tries to provide the tools to have the best possible contract. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size:16px"><strong>What is Contract? </strong></span><br />

Contract is a legally binding agreement that clarifies the responsibilities and obligations of all parties engaged in it in all circumstances. Irrespective of the types and areas, contracts are the lifeline of a functioning market economy. Everything from a credit card transaction to an employment agreement to deals with proprietors and suppliers and investments involves contracts. Without the contracts, no economic activity can exist- a crude form of barter market may be possible but not the vast sophistication of modern industrial and post-industrial activities.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">However, in the context of economic modeling, the contracts that constitute the binding ropes of the entire economy function like a magic box that simplify and reconcile the conflicting interests of the parties. Real contracts are, of course, nothing like that. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/nobel.jpg" style="height:898px; margin-left:10px; margin-right:10px; width:700px" /></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size:16px"><strong>Features of Contract Theory </strong></span><br />

Hart and Holmström developed the Contract Theory as a fertile field of applied research. Over the last few decades, they have also explored its various applications. Their analysis of optimal contractual arrangements lays an intellectual foundation for designing policies and institutions in many areas ranging from bankruptcy legislation to political constitutions. Below are some of the major features of Contracts Theory:</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>1. Government vs Private (who owns what)</strong><br />

Hart’s most interesting research centres on the ways where imperfections of contracts mean that it ultimately does matter who owns what. According to him, there is a meaningful difference between the government that operates a public utility and the government that contracts out the utility to a private operator. He has given an example of a prison, one that is directly managed by the government and another which is contracted out to a private operator. The private prison operator, unlike the government, has strong financial incentives to invest in new methods and processes for bringing down the costs. In this particular case, an incentive to cost reduction will lead to dismal outcomes. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">However, in other cases, contracting out management to incentivise reduction of costs can probably be a good idea. It would make perfect sense for the government to purchase the fighter jets from private aircraft manufacturers rather than to invest the money to manufacture such military hardware. These questions of where to draw the lines between public and private ownership are crucial for many policy issues. Hart’s research offers theoretical tools to help understand such questions.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">For instance, it also makes sense for a private company to own all elements of its supply chain rather than contracting with other companies for supplies. This is often treated as a pure question of financial engineering where the right answer is to own as little as possible to maximise the Return on Equity (ROI). Hart, however, argues that the entity that owns any underlying asset has an incentive to invest in its improvement, which further incentivizes it to own more assets. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>2. Principal-Agent Problem</strong><br />

It is hard to design the right rewards for managers and workers. In this regard, Holmström focuses on different aspects of the contracting relationship, which is one of the complicated interplays between owners, managers, and workers. It is considered to be desirable to “pay for performance,” thus encouraging people to perform their best. Here, Holmström’s main idea is that we cannot just financially reward people for outcomes. Rather we need to make sure the reward system is genuinely based on all the relevant information. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">The pay schemes of a CEO, for example, often fail to meet this standard. Both Nobel Laureates argue that CEOs are likely to be rewarded with bonuses when share prices rise even if the industry or the economy faces a slowdown. It means, managing a company during good times does not reflect the efficiency of a CEO. Conversely (though in practice this happens less often), blaming a CEO for being in charge during a stock market crash or economic recession makes very little sense.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>3. Incentives and Moral Hazard </strong><br />

The contract theory applies ideas about uncertainty to insurance contracts where, in practice, the insured party’s incentives are undermined by the existence of insurance. A paper by Holmström combines the ideas of insurance and compensation to provide a speculative account of why worker-owned companies have not been very successful. According to him, such owners do not get penalised for failures. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">This ends up rewarding the least diligent and least conscientious workers in the company. Here, separating ownership from work creates a group of dedicated punishers who ultimately drive superior performance.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>4. Informed Decision Making</strong><br />

An important aspect regarding the Nobel Prize to Hart and Holmström is there are more economic (micro) theories than very abstract economic (macro) models. Doing empirical studies on how contracts are written and enforced are more interesting and important, which helps to make informed decisions.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Nevertheless, it is difficult for people to make such decisions in real life. It would be utopian and unrealistic to assume that existing practices are optimal. Hart and Holmström use the tools of economic theory to investigate concrete, difficult problems in the design of market structures that rely on the informed decisions.</p>

<p style="text-align: right;"><em>The writer is Director of the Confederation of Nepalese Industries (CNI).</em></p>

',

'status' => true,

'publish_date' => '0000-00-00',

'created' => '2016-11-20 12:20:15',

'modified' => '2016-11-20 12:20:15',

'keywords' => '',

'description' => '',

'sortorder' => '1587',

'feature_article' => true,

'user_id' => '11',

'image1' => null,

'image2' => null,

'image3' => null,

'image4' => null

),

'MagazineIssue' => array(

'id' => '967',

'image' => '20161116023451_cover.JPG',

'sortorder' => '1516',

'published' => true,

'created' => '2016-11-16 14:34:51',

'modified' => '2016-11-16 14:53:11',

'title' => 'November 2016',

'publish_date' => '2016-11-01',

'parent_id' => '0',

'homepage' => true,

'user_id' => '11'

),

'MagazineCategory' => array(

'id' => '103',

'title' => 'Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences 2016',

'sortorder' => '103',

'status' => true,

'created' => '0000-00-00 00:00:00',

'homepage' => false,

'modified' => '2017-05-03 14:54:05'

),

'User' => array(

'password' => '*****',

'id' => '11',

'user_detail_id' => '0',

'group_id' => '24',

'username' => 'nsingha@abhiyan.com.np',

'name' => '',

'email' => 'nsingha@abhiyan.com.np',

'address' => '',

'gender' => '',

'access' => '1',

'phone' => '',

'access_type' => '0',

'activated' => false,

'sortorder' => '0',

'published' => '0',

'created' => '2015-04-08 13:22:59',

'last_login' => '2023-04-16 09:29:47',

'ip' => '172.69.77.43'

),

'MagazineArticleComment' => array(),

'MagazineView' => array(

(int) 0 => array(

'magazine_article_id' => '1626',

'hit' => '3504'

)

)

)

$current_user = null

$logged_in = false

$user = null

$groupId = null

include - APP/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp, line 55

View::_evaluate() - CORE/Cake/View/View.php, line 971

View::_render() - CORE/Cake/View/View.php, line 933

View::render() - CORE/Cake/View/View.php, line 473

Controller::render() - CORE/Cake/Controller/Controller.php, line 968

Dispatcher::_invoke() - CORE/Cake/Routing/Dispatcher.php, line 200

Dispatcher::dispatch() - CORE/Cake/Routing/Dispatcher.php, line 167

[main] - APP/webroot/index.php, line 117

Notice (8): Undefined index: summary [APP/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp, line 62]Code Context<?php

echo $this->Html->meta(array('name' => 'description', 'type' => 'meta', 'content' => $magazineArticle['MagazineArticle']['summary']), null, array('inline' => false));?>

$viewFile = '/var/www/html/newbusinessage.com/app/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp'

$dataForView = array(

'magazineArticle' => array(

'MagazineArticle' => array(

'id' => '1626',

'magazine_issue_id' => '967',

'magazine_category_id' => '103',

'title' => 'Nobel Signs the Contract',

'image' => null,

'short_content' => 'This year’s Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded jointly to economists Dr Oliver Simon D’Arcy Hart and Dr Bengt Holström for their contributions to the development of Contracts Theory. Dr Hart is a British-American who teaches Economics at Harvard',

'content' => '<p style="text-align: center;"><em><span style="font-size:16px">The key idea of the Contract Theory developed by both Nobel Laureates is that there is no such thing as a perfect contract.</span></em></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>--BY HOM NATH GAIRE</strong></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">This year’s Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded jointly to economists Dr Oliver Simon D’Arcy Hart and Dr Bengt Holström for their contributions to the development of Contracts Theory. Dr Hart is a British-American who teaches Economics at Harvard and Dr Holström is Finnish who is a Professor of Economics at MIT. According to the Nobel Foundation, the prize was awarded for their compatible though not collaborative work on developing the theory of contracts into something more robust and informative.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Modern economies are operational and work together by innumerable contracts in one form or another. The theoretical tools, for which Hart and Holmström were awarded, are valuable for the practical understanding of real-life contracts and institutions, as well as potential pitfalls in the contract design.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">"This year’s Economics laureates have developed contract theory, a comprehensive framework for analyzing many diverse issues in contractual design, like performance-based pay for top executives, deductibles and co-pays in insurance, and the privatisation of public-sector activities," says the Nobel Foundation. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Many contractual relationships of modern society include associations between shareholders and top executive management, the rental company and house owners, and/or a public authority and its suppliers. As such relationships typically lead to conflicts of interest, contracts must be properly designed to ensure that the parties take mutually beneficial decisions. In this context, the key idea of the Contract Theory developed by both Nobel Laureates is that there is no such thing as a perfect contract. However, in some cases, it might be ideal to have a document that specifies every possible situation and every possible remedy complete with perfect and immediate information about exactly who did what and when. This is where Hart and Holmström worked independently and came out with the theories and principles, which tries to provide the tools to have the best possible contract. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size:16px"><strong>What is Contract? </strong></span><br />

Contract is a legally binding agreement that clarifies the responsibilities and obligations of all parties engaged in it in all circumstances. Irrespective of the types and areas, contracts are the lifeline of a functioning market economy. Everything from a credit card transaction to an employment agreement to deals with proprietors and suppliers and investments involves contracts. Without the contracts, no economic activity can exist- a crude form of barter market may be possible but not the vast sophistication of modern industrial and post-industrial activities.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">However, in the context of economic modeling, the contracts that constitute the binding ropes of the entire economy function like a magic box that simplify and reconcile the conflicting interests of the parties. Real contracts are, of course, nothing like that. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/nobel.jpg" style="height:898px; margin-left:10px; margin-right:10px; width:700px" /></p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size:16px"><strong>Features of Contract Theory </strong></span><br />

Hart and Holmström developed the Contract Theory as a fertile field of applied research. Over the last few decades, they have also explored its various applications. Their analysis of optimal contractual arrangements lays an intellectual foundation for designing policies and institutions in many areas ranging from bankruptcy legislation to political constitutions. Below are some of the major features of Contracts Theory:</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>1. Government vs Private (who owns what)</strong><br />

Hart’s most interesting research centres on the ways where imperfections of contracts mean that it ultimately does matter who owns what. According to him, there is a meaningful difference between the government that operates a public utility and the government that contracts out the utility to a private operator. He has given an example of a prison, one that is directly managed by the government and another which is contracted out to a private operator. The private prison operator, unlike the government, has strong financial incentives to invest in new methods and processes for bringing down the costs. In this particular case, an incentive to cost reduction will lead to dismal outcomes. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">However, in other cases, contracting out management to incentivise reduction of costs can probably be a good idea. It would make perfect sense for the government to purchase the fighter jets from private aircraft manufacturers rather than to invest the money to manufacture such military hardware. These questions of where to draw the lines between public and private ownership are crucial for many policy issues. Hart’s research offers theoretical tools to help understand such questions.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">For instance, it also makes sense for a private company to own all elements of its supply chain rather than contracting with other companies for supplies. This is often treated as a pure question of financial engineering where the right answer is to own as little as possible to maximise the Return on Equity (ROI). Hart, however, argues that the entity that owns any underlying asset has an incentive to invest in its improvement, which further incentivizes it to own more assets. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>2. Principal-Agent Problem</strong><br />

It is hard to design the right rewards for managers and workers. In this regard, Holmström focuses on different aspects of the contracting relationship, which is one of the complicated interplays between owners, managers, and workers. It is considered to be desirable to “pay for performance,” thus encouraging people to perform their best. Here, Holmström’s main idea is that we cannot just financially reward people for outcomes. Rather we need to make sure the reward system is genuinely based on all the relevant information. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">The pay schemes of a CEO, for example, often fail to meet this standard. Both Nobel Laureates argue that CEOs are likely to be rewarded with bonuses when share prices rise even if the industry or the economy faces a slowdown. It means, managing a company during good times does not reflect the efficiency of a CEO. Conversely (though in practice this happens less often), blaming a CEO for being in charge during a stock market crash or economic recession makes very little sense.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>3. Incentives and Moral Hazard </strong><br />

The contract theory applies ideas about uncertainty to insurance contracts where, in practice, the insured party’s incentives are undermined by the existence of insurance. A paper by Holmström combines the ideas of insurance and compensation to provide a speculative account of why worker-owned companies have not been very successful. According to him, such owners do not get penalised for failures. </p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">This ends up rewarding the least diligent and least conscientious workers in the company. Here, separating ownership from work creates a group of dedicated punishers who ultimately drive superior performance.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>4. Informed Decision Making</strong><br />

An important aspect regarding the Nobel Prize to Hart and Holmström is there are more economic (micro) theories than very abstract economic (macro) models. Doing empirical studies on how contracts are written and enforced are more interesting and important, which helps to make informed decisions.</p>

<p style="text-align: justify;">Nevertheless, it is difficult for people to make such decisions in real life. It would be utopian and unrealistic to assume that existing practices are optimal. Hart and Holmström use the tools of economic theory to investigate concrete, difficult problems in the design of market structures that rely on the informed decisions.</p>

<p style="text-align: right;"><em>The writer is Director of the Confederation of Nepalese Industries (CNI).</em></p>

',

'status' => true,

'publish_date' => '0000-00-00',

'created' => '2016-11-20 12:20:15',