Notice (8): Trying to access array offset on value of type null [APP/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp, line 54]Code Context $user = $this->Session->read('Auth.User');

//find the group of logged user

$groupId = $user['Group']['id'];

$viewFile = '/var/www/html/newbusinessage.com/app/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp'

$dataForView = array(

'magazineArticle' => array(

'MagazineArticle' => array(

'id' => '161',

'magazine_issue_id' => '279',

'magazine_category_id' => '0',

'title' => 'Inclusive Growth Policies of Different Countries',

'image' => null,

'short_content' => null,

'content' => '<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs6.jpg" style="width: 500px; height: 183px; margin: 5px 25px;" /></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong><span style="font-size: 12px;">Bangladesh </span></strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Bangladesh has managed to accelerate overall GDP growth by one percentage point on average every decade -- from 3 per cent in the 1970s to 6 per cent in the last 10 years. Thanks to declining population growth, the acceleration in per capita GDP growth was even higher -- 1.7 percentage points every decade. Acceleration of growth also helped 15 million people leave absolute poverty behind in the past three decades. </div>

<div>

The country’s remarkably steady growth was possible due to a number of factors including population control, financial deepening, macroeconomic stability, and openness in the economy. Building on its social-economic progress so far, Bangladesh now aims to become a middle-income country (MIC) by 2021 to mark its 50th year of independence. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

A new World Bank report, “Bangladesh: Towards Accelerated, Inclusive, and Sustainable Growth—Opportunities and Challenges” says that both GDP growth and remittances would play an important role in attaining middle-income status. According to the report, Bangladesh needs to accelerate GDP growth to 7.5 to 8 per cent and sustain 8 per cent remittance growth to achieve its goal by the next decade. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

To attain the GDP growth, Bangladesh must enhance manufacturing-based export growth and overcome the many hurdles standing in the way, including weak economic governance; overburdened land, power, port, and transportation facilities; and limited success in attracting foreign direct investments in manufacturing. Inadequate infrastructure remains a major bottleneck to growth, which urgently needs </div>

<div>

to be addressed. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

In fact, the critical question for an economy like that of Bangladesh is how inclusive economic growth is and how broadly the benefits of growth are shared. The growth performance of Bangladesh needs to be examined from this perspective. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong>South Africa </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

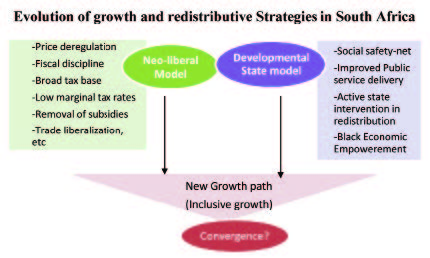

The end of apartheid and the coming to power of the African National Congress (ANC) redefined the development paradigm in South Africa. The new government, after many years of social and economic malaise, adopted a neoliberal view on economic development. As a first step, prudent macroeconomic policies combined with political stability had positive effects on investment and GDP growth. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs7.jpg" style="float: right; margin: 0px 0px 0px 10px; width: 325px; height: 195px;" /></div>

<div>

The first democratic government faced the enormous challenge of having South Africa’s development based on cohesion, inclusion and opportunity. The government therefore launched the Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) programme to rectify inequalities by giving economic opportunities to disadvantaged groups. In that sense, it was the first step towards inclusive growth. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

In 1996, the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) strategy followed the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) that was put in place at the end of the apartheid era in 1994. The GEAR strategy focused on (i) macroeconomic stabilization and (ii) trade and financial liberalization as a priority to foster economic growth, increase employment and reduce poverty. The GEAR was designed along the neo-liberal convictions to economic policy where priority was given to liberalize the economy, allow prices, including exchange rates to be determined through market forces, protect property rights, and improve the environment for doing business. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

In 2011, the country joined the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) as an emerging economy with an important regional influence. </div>

<div>

However, South Africa has a long way to go to achieve desired level of inclusive growth. The huge social problems which </div>

<div>

are apartheid’s legacy remain a threat for the socio-political order. In response, the government adopted an ambitious strategy called the New Growth Path that combined the goal of strong economic growth, job creation and broad economic opportunity in one coherent framework. This effort towards greater inclusion is not without challenges. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Recently, official policy has attempted to reorient government spending to fight deprivation in areas such as access to improved health care and quality of education, provision of decent work, sustainability of livelihoods, and development of economic and social infrastructure. </div>

<div>

The South Africa’s government is one of the few in the World which has committed itself to being a developmental state. The definition of a developmental state has increasingly been given to governments that strive to promote social, economic and political inclusiveness by relying on creative interventions where markets fail and complementing them where they thrive through partnerships. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong>India </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

India’s government has made “inclusive growth” a key element of their policy platform, stating as a goal: “Achieving a growth process in which people in different walks in life… feel that they too benefit significantly from the process.” </div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs8.jpg" style="float: left; margin: 0px 10px 0px 0px; width: 255px; height: 315px;" /></div>

<div>

According to the India Economy Review, Economic growth models do not establish or suggest, however, an explicit causal-effect relationship between a country’s rates of economic growth and the resulting poverty reduction, although policymakers often assume an implicit connection. The current literature provides some guidelines about conditions under which economic growth might be ‘inclusive’ or ‘pro-poor’, although how these concepts should be defined remains controversial. One view is that <span style="font-size: 12px;">growth is ‘pro-poor’ only if the incomes of poor people grow faster than those of the population as a whole, i.e., inequality declines. An alternative position is that growth should be considered to be pro-poor as long as poor people also benefit in absolute terms, as reflected in some agreed poverty measure. </span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Asia's third largest economy India has adopted inclusive growth policy in recent years. The Indian government is stressing that the policy is needed in order to reduce poverty and other social and economic disparities, and also to sustain economic growth. In recognition of this, the planning commission of India had made inclusive growth an explicit goal in the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007-2012). The draft of the Twelfth Five Year Plan (2012-2017) lists twelve strategy challenges which continue the focus on inclusive growth. These include enhancing the capacity for growth, generation of employment, development of infrastructure, improved access to quality education, better healthcare, rural transformation, and sustained agricultural growth. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

India’s growth has primarily benefited urban elite and middle class population who are engaged largely in the fast-growing services sector. However, around 70% of the poor are from rural areas where there is a lack of basic social and infrastructure services, such as healthcare, roads, education, and drinking water.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong>Sri Lanka </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The economy of Sri Lanka experienced a rapid growth over the past few years (8.3 percent in year 2011), mainly due to the cessation of the decades long separatist conflict though the year 2012 shows a slight deceleration of growth (to 6.4 percent). </div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs9.jpg" style="float: right; margin: 0px 0px 0px 10px; width: 300px; height: 198px;" /></div>

<div>

However, despite the rapid growth, still there are certain regions, sectors and groups lagging behind. Despite the improvements in growth in all the provinces, the provincial economic contribution pattern has changed only marginally over years. The pattern of growth has remained skewed towards the Western province. Over the years, almost half of the economic activities remained highly concentrated to the Western Province. In year 2012, the contribution of the economic activities of the Western Province was a little over 44 percent of GDP and interestingly, it keeps coming down at present. </div>

<div>

Growth in the overall economy is driven mainly by industry and services sectors. Although growth of the agriculture sector remained low compared to other two sectors, it kept fluctuating highly. For an instance, the growth of the agriculture sector in year 2012 was 5.8 percent, while it was only 1.4 percent in year 2011. The industry sector recorded a steady growth since 2010, from 8.4 to 10.3 percent in 2012. The marked rate of growth of industry sector is led mainly by the growth in construction sub sector. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The contribution of the agricultural sector to the overall economy has kept decreasing over the years and it is at 11.1 percent at present. The contributions of industry and services sectors increased over time, specially the industry sector records a steady increase. At present, the industry and </div>

<div>

services sectors’ contributions are at 31.5 and 57.5 respectively. However, the patterns of sectoral shares were not uniform across provinces and had changed only marginally over the years. The agriculture share of GDP was more pronounced in provinces of Uva, Northern, North-Central and Sabaragamuwa provinces. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Sri Lanka has adopted "Mahinda Chintana" (President Mahinda Rajapaksha's visions for the future) as the inclusive growth policy. It was the presidential election manifesto of Rajapaksha in 2010, but was later adopted as medium-term growth strategy for the country. It envisioned Sri Lanka to be changed as "Wonder of Asia" through inclusive growth acceleration and implementing policies that promote the inclusion of all segments of society in the growth process. After the end of long brutal civil war in 2009, Sri Lanka is witnessing strong economic growth. But, along with it, the rise of inequality is also said to be growing in alarming pace. The Sri Lankan inclusive growth policy includes, increasing investments in various sectors, improving productivity of those investments through innovation policies, skills development and macroeconomic stability.</div>

<div>

<strong> </strong></div>

<div>

<strong>Bhutan </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

‘Gross National Happiness’ (GNH) is the philosophy which forms the cornerstone of Bhutan’s development and which Bhutan is succeeding in implementing. Introduced by the Fourth King of Bhutan in the 1970s, GNH presents an alternative model for development which places equal weight on the social, spiritual, intellectual, cultural and emotional needs of a society as it does on material and economic gain. The GNH philosophy today garners considerable attention as many nations, both developed and developing, assess the merits of development and, in particular, the extent <span style="font-size: 12px;">to which their people’s sense of well-being and happiness is reflected by their levels of material and economic gain. </span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs10.jpg" style="float: left; margin: 0px 10px 0px 0px; width: 300px; height: 272px;" /></div>

<div>

Economic growth moderated to 7.5 per cent in fiscal year 2012 (ended 30 June 2012) from 10.0 per cent a year earlier. The slowdown reflected credit measures taken by the Royal Monetary Authority (RMA) to curb Bhutan's escalating balance of payments deficit with India and alleviate the rupee liquidity crunch. Both general and specific credit restrictions were implemented to constrain imports that are a large component of consumer and investment spending. Reflecting the measures, growth in consumption, which accounts for about three-fifths of gross domestic product (GDP), slowed to 7.8 per cent in FY2012 from 10.0 per cent in FY2011. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Inherent in its Buddhist philosophy and committed to the overarching goals Gross National Happiness – sustainable development, preservation of cultural values, conservation of the environment and good governance - - Bhutan today enjoys a number of development assets, including strong ownership of the development process, low levels of corruption, robust institutions, a well educated and dedicated civil service and visionary leadership. Bhutan is well poised to consolidate and expand on the numerous impressive gains it has achieved since the advent of development planning and its recent smooth transition to democracy. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

According to Asian Development Outlook 2013, growth is expected to recover in FY2013 and reach 8.6 per cent, driven mainly by hydropower and tourism. The contribution of the service sector to growth is expected to improve as the government develops the Bhutan’s tourism potential. As this trend is likely to continue, 8.5 per cent growth is expected in FY2014.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong>Brazil </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Countries that pursued inequality-reducing strategies have been warned that growth will be affected, and hence that poverty increases. The harbingers of doom advocated a growth-focused strategy. Their assumption was that the income of the poor rises in direct proportion to economic growth. The truth is more like this: economies with more equal income distribution are likely to achieve higher rates of poverty reduction than very unequal countries. Let’s see if this is the case in Brazil. </div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs11.jpg" style="float: right; margin: 0px 0px 0px 10px; width: 300px; height: 173px;" /></div>

<div>

Inequality in Brazil, as measured by the Gini coefficient, fell from 0.59 in 2001 to <span style="font-size: 12px;">0.53 in 2007. Much remains unknown about why inequality has fallen, but two sets of known causes stand out. The first consists of improvements in education. In the early and mid 1990s, for example, the workforce gained more equal access to education. This is because of universal admission to primary schooling and lower repetition rates. </span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The impact of improved access to education on primary income distribution was 0.2 Gini points per year from 1995 onwards. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The second set of factors that reduce inequality are direct cash transfers from the state to families and individuals. These transfers improve secondary income distribution. At the same time, conditional cash transfers, such as Bolsa Família, deliver substantial amounts directly to the poorest families. Together, these changes lead to reductions in inequality of another 0.2 Gini points per year.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

A virtuous cycle of increases in the income of poorer families, together with wage growth, has enlarged the domestic market. Greater consumption of mass-market goods has led to growing labour demand for these same families, spurring further increases in their income and purchasing power. For instance, unemployment fell by 22 per cent between 2004 and 2007. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Brazil still has a high level of inequality and progress in being made towards lowering it. It is too early to say with certainty, but one reason why the financial and economic crisis did not hit Brazil as hard as other countries may be the growing domestic market and changes in the structure of demand created in the last decade. These, in turn were spurred by this virtuous pattern of improved income distribution. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size:11px;"><em>(Source: International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth)</em></span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

</div>',

'status' => true,

'publish_date' => '0000-00-00',

'created' => '2013-07-14 00:00:00',

'modified' => '2013-07-14 00:00:00',

'keywords' => 'new business age cover story news & articles, cover story news & articles from new business age nepal, cover story headlines from nepal, current and latest cover story news from nepal, economic news from nepal, nepali cover story economic news and events, ongoing cover story news of nepal',

'description' => 'new business age cover story news & articles, cover story news & articles from new business age nepal, cover story headlines from nepal, current and latest cover story news from nepal, economic news from nepal, nepali cover story economic news and events, ongoing cover story news of nepal',

'sortorder' => '141',

'feature_article' => true,

'user_id' => '0',

'image1' => null,

'image2' => null,

'image3' => null,

'image4' => null

),

'MagazineIssue' => array(

'id' => '279',

'image' => 'small_1372930595.jpg',

'sortorder' => '186',

'published' => true,

'created' => '2013-07-04 02:37:42',

'modified' => null,

'title' => 'Cover Story',

'publish_date' => '2013-07-01',

'parent_id' => '234',

'homepage' => false,

'user_id' => '0'

),

'MagazineCategory' => array(

'id' => null,

'title' => null,

'sortorder' => null,

'status' => null,

'created' => null,

'homepage' => null,

'modified' => null

),

'User' => array(

'password' => '*****',

'id' => null,

'user_detail_id' => null,

'group_id' => null,

'username' => null,

'name' => null,

'email' => null,

'address' => null,

'gender' => null,

'access' => null,

'phone' => null,

'access_type' => null,

'activated' => null,

'sortorder' => null,

'published' => null,

'created' => null,

'last_login' => null,

'ip' => null

),

'MagazineArticleComment' => array(),

'MagazineView' => array(

(int) 0 => array(

[maximum depth reached]

)

)

),

'current_user' => null,

'logged_in' => false

)

$magazineArticle = array(

'MagazineArticle' => array(

'id' => '161',

'magazine_issue_id' => '279',

'magazine_category_id' => '0',

'title' => 'Inclusive Growth Policies of Different Countries',

'image' => null,

'short_content' => null,

'content' => '<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs6.jpg" style="width: 500px; height: 183px; margin: 5px 25px;" /></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong><span style="font-size: 12px;">Bangladesh </span></strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Bangladesh has managed to accelerate overall GDP growth by one percentage point on average every decade -- from 3 per cent in the 1970s to 6 per cent in the last 10 years. Thanks to declining population growth, the acceleration in per capita GDP growth was even higher -- 1.7 percentage points every decade. Acceleration of growth also helped 15 million people leave absolute poverty behind in the past three decades. </div>

<div>

The country’s remarkably steady growth was possible due to a number of factors including population control, financial deepening, macroeconomic stability, and openness in the economy. Building on its social-economic progress so far, Bangladesh now aims to become a middle-income country (MIC) by 2021 to mark its 50th year of independence. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

A new World Bank report, “Bangladesh: Towards Accelerated, Inclusive, and Sustainable Growth—Opportunities and Challenges” says that both GDP growth and remittances would play an important role in attaining middle-income status. According to the report, Bangladesh needs to accelerate GDP growth to 7.5 to 8 per cent and sustain 8 per cent remittance growth to achieve its goal by the next decade. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

To attain the GDP growth, Bangladesh must enhance manufacturing-based export growth and overcome the many hurdles standing in the way, including weak economic governance; overburdened land, power, port, and transportation facilities; and limited success in attracting foreign direct investments in manufacturing. Inadequate infrastructure remains a major bottleneck to growth, which urgently needs </div>

<div>

to be addressed. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

In fact, the critical question for an economy like that of Bangladesh is how inclusive economic growth is and how broadly the benefits of growth are shared. The growth performance of Bangladesh needs to be examined from this perspective. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong>South Africa </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The end of apartheid and the coming to power of the African National Congress (ANC) redefined the development paradigm in South Africa. The new government, after many years of social and economic malaise, adopted a neoliberal view on economic development. As a first step, prudent macroeconomic policies combined with political stability had positive effects on investment and GDP growth. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs7.jpg" style="float: right; margin: 0px 0px 0px 10px; width: 325px; height: 195px;" /></div>

<div>

The first democratic government faced the enormous challenge of having South Africa’s development based on cohesion, inclusion and opportunity. The government therefore launched the Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) programme to rectify inequalities by giving economic opportunities to disadvantaged groups. In that sense, it was the first step towards inclusive growth. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

In 1996, the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) strategy followed the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) that was put in place at the end of the apartheid era in 1994. The GEAR strategy focused on (i) macroeconomic stabilization and (ii) trade and financial liberalization as a priority to foster economic growth, increase employment and reduce poverty. The GEAR was designed along the neo-liberal convictions to economic policy where priority was given to liberalize the economy, allow prices, including exchange rates to be determined through market forces, protect property rights, and improve the environment for doing business. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

In 2011, the country joined the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) as an emerging economy with an important regional influence. </div>

<div>

However, South Africa has a long way to go to achieve desired level of inclusive growth. The huge social problems which </div>

<div>

are apartheid’s legacy remain a threat for the socio-political order. In response, the government adopted an ambitious strategy called the New Growth Path that combined the goal of strong economic growth, job creation and broad economic opportunity in one coherent framework. This effort towards greater inclusion is not without challenges. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Recently, official policy has attempted to reorient government spending to fight deprivation in areas such as access to improved health care and quality of education, provision of decent work, sustainability of livelihoods, and development of economic and social infrastructure. </div>

<div>

The South Africa’s government is one of the few in the World which has committed itself to being a developmental state. The definition of a developmental state has increasingly been given to governments that strive to promote social, economic and political inclusiveness by relying on creative interventions where markets fail and complementing them where they thrive through partnerships. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong>India </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

India’s government has made “inclusive growth” a key element of their policy platform, stating as a goal: “Achieving a growth process in which people in different walks in life… feel that they too benefit significantly from the process.” </div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs8.jpg" style="float: left; margin: 0px 10px 0px 0px; width: 255px; height: 315px;" /></div>

<div>

According to the India Economy Review, Economic growth models do not establish or suggest, however, an explicit causal-effect relationship between a country’s rates of economic growth and the resulting poverty reduction, although policymakers often assume an implicit connection. The current literature provides some guidelines about conditions under which economic growth might be ‘inclusive’ or ‘pro-poor’, although how these concepts should be defined remains controversial. One view is that <span style="font-size: 12px;">growth is ‘pro-poor’ only if the incomes of poor people grow faster than those of the population as a whole, i.e., inequality declines. An alternative position is that growth should be considered to be pro-poor as long as poor people also benefit in absolute terms, as reflected in some agreed poverty measure. </span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Asia's third largest economy India has adopted inclusive growth policy in recent years. The Indian government is stressing that the policy is needed in order to reduce poverty and other social and economic disparities, and also to sustain economic growth. In recognition of this, the planning commission of India had made inclusive growth an explicit goal in the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007-2012). The draft of the Twelfth Five Year Plan (2012-2017) lists twelve strategy challenges which continue the focus on inclusive growth. These include enhancing the capacity for growth, generation of employment, development of infrastructure, improved access to quality education, better healthcare, rural transformation, and sustained agricultural growth. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

India’s growth has primarily benefited urban elite and middle class population who are engaged largely in the fast-growing services sector. However, around 70% of the poor are from rural areas where there is a lack of basic social and infrastructure services, such as healthcare, roads, education, and drinking water.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong>Sri Lanka </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The economy of Sri Lanka experienced a rapid growth over the past few years (8.3 percent in year 2011), mainly due to the cessation of the decades long separatist conflict though the year 2012 shows a slight deceleration of growth (to 6.4 percent). </div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs9.jpg" style="float: right; margin: 0px 0px 0px 10px; width: 300px; height: 198px;" /></div>

<div>

However, despite the rapid growth, still there are certain regions, sectors and groups lagging behind. Despite the improvements in growth in all the provinces, the provincial economic contribution pattern has changed only marginally over years. The pattern of growth has remained skewed towards the Western province. Over the years, almost half of the economic activities remained highly concentrated to the Western Province. In year 2012, the contribution of the economic activities of the Western Province was a little over 44 percent of GDP and interestingly, it keeps coming down at present. </div>

<div>

Growth in the overall economy is driven mainly by industry and services sectors. Although growth of the agriculture sector remained low compared to other two sectors, it kept fluctuating highly. For an instance, the growth of the agriculture sector in year 2012 was 5.8 percent, while it was only 1.4 percent in year 2011. The industry sector recorded a steady growth since 2010, from 8.4 to 10.3 percent in 2012. The marked rate of growth of industry sector is led mainly by the growth in construction sub sector. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The contribution of the agricultural sector to the overall economy has kept decreasing over the years and it is at 11.1 percent at present. The contributions of industry and services sectors increased over time, specially the industry sector records a steady increase. At present, the industry and </div>

<div>

services sectors’ contributions are at 31.5 and 57.5 respectively. However, the patterns of sectoral shares were not uniform across provinces and had changed only marginally over the years. The agriculture share of GDP was more pronounced in provinces of Uva, Northern, North-Central and Sabaragamuwa provinces. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Sri Lanka has adopted "Mahinda Chintana" (President Mahinda Rajapaksha's visions for the future) as the inclusive growth policy. It was the presidential election manifesto of Rajapaksha in 2010, but was later adopted as medium-term growth strategy for the country. It envisioned Sri Lanka to be changed as "Wonder of Asia" through inclusive growth acceleration and implementing policies that promote the inclusion of all segments of society in the growth process. After the end of long brutal civil war in 2009, Sri Lanka is witnessing strong economic growth. But, along with it, the rise of inequality is also said to be growing in alarming pace. The Sri Lankan inclusive growth policy includes, increasing investments in various sectors, improving productivity of those investments through innovation policies, skills development and macroeconomic stability.</div>

<div>

<strong> </strong></div>

<div>

<strong>Bhutan </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

‘Gross National Happiness’ (GNH) is the philosophy which forms the cornerstone of Bhutan’s development and which Bhutan is succeeding in implementing. Introduced by the Fourth King of Bhutan in the 1970s, GNH presents an alternative model for development which places equal weight on the social, spiritual, intellectual, cultural and emotional needs of a society as it does on material and economic gain. The GNH philosophy today garners considerable attention as many nations, both developed and developing, assess the merits of development and, in particular, the extent <span style="font-size: 12px;">to which their people’s sense of well-being and happiness is reflected by their levels of material and economic gain. </span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs10.jpg" style="float: left; margin: 0px 10px 0px 0px; width: 300px; height: 272px;" /></div>

<div>

Economic growth moderated to 7.5 per cent in fiscal year 2012 (ended 30 June 2012) from 10.0 per cent a year earlier. The slowdown reflected credit measures taken by the Royal Monetary Authority (RMA) to curb Bhutan's escalating balance of payments deficit with India and alleviate the rupee liquidity crunch. Both general and specific credit restrictions were implemented to constrain imports that are a large component of consumer and investment spending. Reflecting the measures, growth in consumption, which accounts for about three-fifths of gross domestic product (GDP), slowed to 7.8 per cent in FY2012 from 10.0 per cent in FY2011. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Inherent in its Buddhist philosophy and committed to the overarching goals Gross National Happiness – sustainable development, preservation of cultural values, conservation of the environment and good governance - - Bhutan today enjoys a number of development assets, including strong ownership of the development process, low levels of corruption, robust institutions, a well educated and dedicated civil service and visionary leadership. Bhutan is well poised to consolidate and expand on the numerous impressive gains it has achieved since the advent of development planning and its recent smooth transition to democracy. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

According to Asian Development Outlook 2013, growth is expected to recover in FY2013 and reach 8.6 per cent, driven mainly by hydropower and tourism. The contribution of the service sector to growth is expected to improve as the government develops the Bhutan’s tourism potential. As this trend is likely to continue, 8.5 per cent growth is expected in FY2014.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong>Brazil </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Countries that pursued inequality-reducing strategies have been warned that growth will be affected, and hence that poverty increases. The harbingers of doom advocated a growth-focused strategy. Their assumption was that the income of the poor rises in direct proportion to economic growth. The truth is more like this: economies with more equal income distribution are likely to achieve higher rates of poverty reduction than very unequal countries. Let’s see if this is the case in Brazil. </div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs11.jpg" style="float: right; margin: 0px 0px 0px 10px; width: 300px; height: 173px;" /></div>

<div>

Inequality in Brazil, as measured by the Gini coefficient, fell from 0.59 in 2001 to <span style="font-size: 12px;">0.53 in 2007. Much remains unknown about why inequality has fallen, but two sets of known causes stand out. The first consists of improvements in education. In the early and mid 1990s, for example, the workforce gained more equal access to education. This is because of universal admission to primary schooling and lower repetition rates. </span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The impact of improved access to education on primary income distribution was 0.2 Gini points per year from 1995 onwards. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The second set of factors that reduce inequality are direct cash transfers from the state to families and individuals. These transfers improve secondary income distribution. At the same time, conditional cash transfers, such as Bolsa Família, deliver substantial amounts directly to the poorest families. Together, these changes lead to reductions in inequality of another 0.2 Gini points per year.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

A virtuous cycle of increases in the income of poorer families, together with wage growth, has enlarged the domestic market. Greater consumption of mass-market goods has led to growing labour demand for these same families, spurring further increases in their income and purchasing power. For instance, unemployment fell by 22 per cent between 2004 and 2007. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Brazil still has a high level of inequality and progress in being made towards lowering it. It is too early to say with certainty, but one reason why the financial and economic crisis did not hit Brazil as hard as other countries may be the growing domestic market and changes in the structure of demand created in the last decade. These, in turn were spurred by this virtuous pattern of improved income distribution. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size:11px;"><em>(Source: International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth)</em></span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

</div>',

'status' => true,

'publish_date' => '0000-00-00',

'created' => '2013-07-14 00:00:00',

'modified' => '2013-07-14 00:00:00',

'keywords' => 'new business age cover story news & articles, cover story news & articles from new business age nepal, cover story headlines from nepal, current and latest cover story news from nepal, economic news from nepal, nepali cover story economic news and events, ongoing cover story news of nepal',

'description' => 'new business age cover story news & articles, cover story news & articles from new business age nepal, cover story headlines from nepal, current and latest cover story news from nepal, economic news from nepal, nepali cover story economic news and events, ongoing cover story news of nepal',

'sortorder' => '141',

'feature_article' => true,

'user_id' => '0',

'image1' => null,

'image2' => null,

'image3' => null,

'image4' => null

),

'MagazineIssue' => array(

'id' => '279',

'image' => 'small_1372930595.jpg',

'sortorder' => '186',

'published' => true,

'created' => '2013-07-04 02:37:42',

'modified' => null,

'title' => 'Cover Story',

'publish_date' => '2013-07-01',

'parent_id' => '234',

'homepage' => false,

'user_id' => '0'

),

'MagazineCategory' => array(

'id' => null,

'title' => null,

'sortorder' => null,

'status' => null,

'created' => null,

'homepage' => null,

'modified' => null

),

'User' => array(

'password' => '*****',

'id' => null,

'user_detail_id' => null,

'group_id' => null,

'username' => null,

'name' => null,

'email' => null,

'address' => null,

'gender' => null,

'access' => null,

'phone' => null,

'access_type' => null,

'activated' => null,

'sortorder' => null,

'published' => null,

'created' => null,

'last_login' => null,

'ip' => null

),

'MagazineArticleComment' => array(),

'MagazineView' => array(

(int) 0 => array(

'magazine_article_id' => '161',

'hit' => '1572'

)

)

)

$current_user = null

$logged_in = false

$user = null

include - APP/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp, line 54

View::_evaluate() - CORE/Cake/View/View.php, line 971

View::_render() - CORE/Cake/View/View.php, line 933

View::render() - CORE/Cake/View/View.php, line 473

Controller::render() - CORE/Cake/Controller/Controller.php, line 968

Dispatcher::_invoke() - CORE/Cake/Routing/Dispatcher.php, line 200

Dispatcher::dispatch() - CORE/Cake/Routing/Dispatcher.php, line 167

[main] - APP/webroot/index.php, line 117

Notice (8): Trying to access array offset on value of type null [APP/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp, line 54]Code Context $user = $this->Session->read('Auth.User');

//find the group of logged user

$groupId = $user['Group']['id'];

$viewFile = '/var/www/html/newbusinessage.com/app/View/MagazineArticles/view.ctp'

$dataForView = array(

'magazineArticle' => array(

'MagazineArticle' => array(

'id' => '161',

'magazine_issue_id' => '279',

'magazine_category_id' => '0',

'title' => 'Inclusive Growth Policies of Different Countries',

'image' => null,

'short_content' => null,

'content' => '<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs6.jpg" style="width: 500px; height: 183px; margin: 5px 25px;" /></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong><span style="font-size: 12px;">Bangladesh </span></strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Bangladesh has managed to accelerate overall GDP growth by one percentage point on average every decade -- from 3 per cent in the 1970s to 6 per cent in the last 10 years. Thanks to declining population growth, the acceleration in per capita GDP growth was even higher -- 1.7 percentage points every decade. Acceleration of growth also helped 15 million people leave absolute poverty behind in the past three decades. </div>

<div>

The country’s remarkably steady growth was possible due to a number of factors including population control, financial deepening, macroeconomic stability, and openness in the economy. Building on its social-economic progress so far, Bangladesh now aims to become a middle-income country (MIC) by 2021 to mark its 50th year of independence. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

A new World Bank report, “Bangladesh: Towards Accelerated, Inclusive, and Sustainable Growth—Opportunities and Challenges” says that both GDP growth and remittances would play an important role in attaining middle-income status. According to the report, Bangladesh needs to accelerate GDP growth to 7.5 to 8 per cent and sustain 8 per cent remittance growth to achieve its goal by the next decade. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

To attain the GDP growth, Bangladesh must enhance manufacturing-based export growth and overcome the many hurdles standing in the way, including weak economic governance; overburdened land, power, port, and transportation facilities; and limited success in attracting foreign direct investments in manufacturing. Inadequate infrastructure remains a major bottleneck to growth, which urgently needs </div>

<div>

to be addressed. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

In fact, the critical question for an economy like that of Bangladesh is how inclusive economic growth is and how broadly the benefits of growth are shared. The growth performance of Bangladesh needs to be examined from this perspective. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong>South Africa </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The end of apartheid and the coming to power of the African National Congress (ANC) redefined the development paradigm in South Africa. The new government, after many years of social and economic malaise, adopted a neoliberal view on economic development. As a first step, prudent macroeconomic policies combined with political stability had positive effects on investment and GDP growth. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs7.jpg" style="float: right; margin: 0px 0px 0px 10px; width: 325px; height: 195px;" /></div>

<div>

The first democratic government faced the enormous challenge of having South Africa’s development based on cohesion, inclusion and opportunity. The government therefore launched the Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) programme to rectify inequalities by giving economic opportunities to disadvantaged groups. In that sense, it was the first step towards inclusive growth. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

In 1996, the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) strategy followed the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) that was put in place at the end of the apartheid era in 1994. The GEAR strategy focused on (i) macroeconomic stabilization and (ii) trade and financial liberalization as a priority to foster economic growth, increase employment and reduce poverty. The GEAR was designed along the neo-liberal convictions to economic policy where priority was given to liberalize the economy, allow prices, including exchange rates to be determined through market forces, protect property rights, and improve the environment for doing business. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

In 2011, the country joined the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) as an emerging economy with an important regional influence. </div>

<div>

However, South Africa has a long way to go to achieve desired level of inclusive growth. The huge social problems which </div>

<div>

are apartheid’s legacy remain a threat for the socio-political order. In response, the government adopted an ambitious strategy called the New Growth Path that combined the goal of strong economic growth, job creation and broad economic opportunity in one coherent framework. This effort towards greater inclusion is not without challenges. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Recently, official policy has attempted to reorient government spending to fight deprivation in areas such as access to improved health care and quality of education, provision of decent work, sustainability of livelihoods, and development of economic and social infrastructure. </div>

<div>

The South Africa’s government is one of the few in the World which has committed itself to being a developmental state. The definition of a developmental state has increasingly been given to governments that strive to promote social, economic and political inclusiveness by relying on creative interventions where markets fail and complementing them where they thrive through partnerships. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong>India </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

India’s government has made “inclusive growth” a key element of their policy platform, stating as a goal: “Achieving a growth process in which people in different walks in life… feel that they too benefit significantly from the process.” </div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs8.jpg" style="float: left; margin: 0px 10px 0px 0px; width: 255px; height: 315px;" /></div>

<div>

According to the India Economy Review, Economic growth models do not establish or suggest, however, an explicit causal-effect relationship between a country’s rates of economic growth and the resulting poverty reduction, although policymakers often assume an implicit connection. The current literature provides some guidelines about conditions under which economic growth might be ‘inclusive’ or ‘pro-poor’, although how these concepts should be defined remains controversial. One view is that <span style="font-size: 12px;">growth is ‘pro-poor’ only if the incomes of poor people grow faster than those of the population as a whole, i.e., inequality declines. An alternative position is that growth should be considered to be pro-poor as long as poor people also benefit in absolute terms, as reflected in some agreed poverty measure. </span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Asia's third largest economy India has adopted inclusive growth policy in recent years. The Indian government is stressing that the policy is needed in order to reduce poverty and other social and economic disparities, and also to sustain economic growth. In recognition of this, the planning commission of India had made inclusive growth an explicit goal in the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007-2012). The draft of the Twelfth Five Year Plan (2012-2017) lists twelve strategy challenges which continue the focus on inclusive growth. These include enhancing the capacity for growth, generation of employment, development of infrastructure, improved access to quality education, better healthcare, rural transformation, and sustained agricultural growth. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

India’s growth has primarily benefited urban elite and middle class population who are engaged largely in the fast-growing services sector. However, around 70% of the poor are from rural areas where there is a lack of basic social and infrastructure services, such as healthcare, roads, education, and drinking water.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong>Sri Lanka </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The economy of Sri Lanka experienced a rapid growth over the past few years (8.3 percent in year 2011), mainly due to the cessation of the decades long separatist conflict though the year 2012 shows a slight deceleration of growth (to 6.4 percent). </div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs9.jpg" style="float: right; margin: 0px 0px 0px 10px; width: 300px; height: 198px;" /></div>

<div>

However, despite the rapid growth, still there are certain regions, sectors and groups lagging behind. Despite the improvements in growth in all the provinces, the provincial economic contribution pattern has changed only marginally over years. The pattern of growth has remained skewed towards the Western province. Over the years, almost half of the economic activities remained highly concentrated to the Western Province. In year 2012, the contribution of the economic activities of the Western Province was a little over 44 percent of GDP and interestingly, it keeps coming down at present. </div>

<div>

Growth in the overall economy is driven mainly by industry and services sectors. Although growth of the agriculture sector remained low compared to other two sectors, it kept fluctuating highly. For an instance, the growth of the agriculture sector in year 2012 was 5.8 percent, while it was only 1.4 percent in year 2011. The industry sector recorded a steady growth since 2010, from 8.4 to 10.3 percent in 2012. The marked rate of growth of industry sector is led mainly by the growth in construction sub sector. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The contribution of the agricultural sector to the overall economy has kept decreasing over the years and it is at 11.1 percent at present. The contributions of industry and services sectors increased over time, specially the industry sector records a steady increase. At present, the industry and </div>

<div>

services sectors’ contributions are at 31.5 and 57.5 respectively. However, the patterns of sectoral shares were not uniform across provinces and had changed only marginally over the years. The agriculture share of GDP was more pronounced in provinces of Uva, Northern, North-Central and Sabaragamuwa provinces. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Sri Lanka has adopted "Mahinda Chintana" (President Mahinda Rajapaksha's visions for the future) as the inclusive growth policy. It was the presidential election manifesto of Rajapaksha in 2010, but was later adopted as medium-term growth strategy for the country. It envisioned Sri Lanka to be changed as "Wonder of Asia" through inclusive growth acceleration and implementing policies that promote the inclusion of all segments of society in the growth process. After the end of long brutal civil war in 2009, Sri Lanka is witnessing strong economic growth. But, along with it, the rise of inequality is also said to be growing in alarming pace. The Sri Lankan inclusive growth policy includes, increasing investments in various sectors, improving productivity of those investments through innovation policies, skills development and macroeconomic stability.</div>

<div>

<strong> </strong></div>

<div>

<strong>Bhutan </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

‘Gross National Happiness’ (GNH) is the philosophy which forms the cornerstone of Bhutan’s development and which Bhutan is succeeding in implementing. Introduced by the Fourth King of Bhutan in the 1970s, GNH presents an alternative model for development which places equal weight on the social, spiritual, intellectual, cultural and emotional needs of a society as it does on material and economic gain. The GNH philosophy today garners considerable attention as many nations, both developed and developing, assess the merits of development and, in particular, the extent <span style="font-size: 12px;">to which their people’s sense of well-being and happiness is reflected by their levels of material and economic gain. </span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs10.jpg" style="float: left; margin: 0px 10px 0px 0px; width: 300px; height: 272px;" /></div>

<div>

Economic growth moderated to 7.5 per cent in fiscal year 2012 (ended 30 June 2012) from 10.0 per cent a year earlier. The slowdown reflected credit measures taken by the Royal Monetary Authority (RMA) to curb Bhutan's escalating balance of payments deficit with India and alleviate the rupee liquidity crunch. Both general and specific credit restrictions were implemented to constrain imports that are a large component of consumer and investment spending. Reflecting the measures, growth in consumption, which accounts for about three-fifths of gross domestic product (GDP), slowed to 7.8 per cent in FY2012 from 10.0 per cent in FY2011. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Inherent in its Buddhist philosophy and committed to the overarching goals Gross National Happiness – sustainable development, preservation of cultural values, conservation of the environment and good governance - - Bhutan today enjoys a number of development assets, including strong ownership of the development process, low levels of corruption, robust institutions, a well educated and dedicated civil service and visionary leadership. Bhutan is well poised to consolidate and expand on the numerous impressive gains it has achieved since the advent of development planning and its recent smooth transition to democracy. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

According to Asian Development Outlook 2013, growth is expected to recover in FY2013 and reach 8.6 per cent, driven mainly by hydropower and tourism. The contribution of the service sector to growth is expected to improve as the government develops the Bhutan’s tourism potential. As this trend is likely to continue, 8.5 per cent growth is expected in FY2014.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong>Brazil </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Countries that pursued inequality-reducing strategies have been warned that growth will be affected, and hence that poverty increases. The harbingers of doom advocated a growth-focused strategy. Their assumption was that the income of the poor rises in direct proportion to economic growth. The truth is more like this: economies with more equal income distribution are likely to achieve higher rates of poverty reduction than very unequal countries. Let’s see if this is the case in Brazil. </div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs11.jpg" style="float: right; margin: 0px 0px 0px 10px; width: 300px; height: 173px;" /></div>

<div>

Inequality in Brazil, as measured by the Gini coefficient, fell from 0.59 in 2001 to <span style="font-size: 12px;">0.53 in 2007. Much remains unknown about why inequality has fallen, but two sets of known causes stand out. The first consists of improvements in education. In the early and mid 1990s, for example, the workforce gained more equal access to education. This is because of universal admission to primary schooling and lower repetition rates. </span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The impact of improved access to education on primary income distribution was 0.2 Gini points per year from 1995 onwards. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The second set of factors that reduce inequality are direct cash transfers from the state to families and individuals. These transfers improve secondary income distribution. At the same time, conditional cash transfers, such as Bolsa Família, deliver substantial amounts directly to the poorest families. Together, these changes lead to reductions in inequality of another 0.2 Gini points per year.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

A virtuous cycle of increases in the income of poorer families, together with wage growth, has enlarged the domestic market. Greater consumption of mass-market goods has led to growing labour demand for these same families, spurring further increases in their income and purchasing power. For instance, unemployment fell by 22 per cent between 2004 and 2007. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Brazil still has a high level of inequality and progress in being made towards lowering it. It is too early to say with certainty, but one reason why the financial and economic crisis did not hit Brazil as hard as other countries may be the growing domestic market and changes in the structure of demand created in the last decade. These, in turn were spurred by this virtuous pattern of improved income distribution. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size:11px;"><em>(Source: International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth)</em></span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

</div>',

'status' => true,

'publish_date' => '0000-00-00',

'created' => '2013-07-14 00:00:00',

'modified' => '2013-07-14 00:00:00',

'keywords' => 'new business age cover story news & articles, cover story news & articles from new business age nepal, cover story headlines from nepal, current and latest cover story news from nepal, economic news from nepal, nepali cover story economic news and events, ongoing cover story news of nepal',

'description' => 'new business age cover story news & articles, cover story news & articles from new business age nepal, cover story headlines from nepal, current and latest cover story news from nepal, economic news from nepal, nepali cover story economic news and events, ongoing cover story news of nepal',

'sortorder' => '141',

'feature_article' => true,

'user_id' => '0',

'image1' => null,

'image2' => null,

'image3' => null,

'image4' => null

),

'MagazineIssue' => array(

'id' => '279',

'image' => 'small_1372930595.jpg',

'sortorder' => '186',

'published' => true,

'created' => '2013-07-04 02:37:42',

'modified' => null,

'title' => 'Cover Story',

'publish_date' => '2013-07-01',

'parent_id' => '234',

'homepage' => false,

'user_id' => '0'

),

'MagazineCategory' => array(

'id' => null,

'title' => null,

'sortorder' => null,

'status' => null,

'created' => null,

'homepage' => null,

'modified' => null

),

'User' => array(

'password' => '*****',

'id' => null,

'user_detail_id' => null,

'group_id' => null,

'username' => null,

'name' => null,

'email' => null,

'address' => null,

'gender' => null,

'access' => null,

'phone' => null,

'access_type' => null,

'activated' => null,

'sortorder' => null,

'published' => null,

'created' => null,

'last_login' => null,

'ip' => null

),

'MagazineArticleComment' => array(),

'MagazineView' => array(

(int) 0 => array(

[maximum depth reached]

)

)

),

'current_user' => null,

'logged_in' => false

)

$magazineArticle = array(

'MagazineArticle' => array(

'id' => '161',

'magazine_issue_id' => '279',

'magazine_category_id' => '0',

'title' => 'Inclusive Growth Policies of Different Countries',

'image' => null,

'short_content' => null,

'content' => '<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs6.jpg" style="width: 500px; height: 183px; margin: 5px 25px;" /></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong><span style="font-size: 12px;">Bangladesh </span></strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Bangladesh has managed to accelerate overall GDP growth by one percentage point on average every decade -- from 3 per cent in the 1970s to 6 per cent in the last 10 years. Thanks to declining population growth, the acceleration in per capita GDP growth was even higher -- 1.7 percentage points every decade. Acceleration of growth also helped 15 million people leave absolute poverty behind in the past three decades. </div>

<div>

The country’s remarkably steady growth was possible due to a number of factors including population control, financial deepening, macroeconomic stability, and openness in the economy. Building on its social-economic progress so far, Bangladesh now aims to become a middle-income country (MIC) by 2021 to mark its 50th year of independence. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

A new World Bank report, “Bangladesh: Towards Accelerated, Inclusive, and Sustainable Growth—Opportunities and Challenges” says that both GDP growth and remittances would play an important role in attaining middle-income status. According to the report, Bangladesh needs to accelerate GDP growth to 7.5 to 8 per cent and sustain 8 per cent remittance growth to achieve its goal by the next decade. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

To attain the GDP growth, Bangladesh must enhance manufacturing-based export growth and overcome the many hurdles standing in the way, including weak economic governance; overburdened land, power, port, and transportation facilities; and limited success in attracting foreign direct investments in manufacturing. Inadequate infrastructure remains a major bottleneck to growth, which urgently needs </div>

<div>

to be addressed. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

In fact, the critical question for an economy like that of Bangladesh is how inclusive economic growth is and how broadly the benefits of growth are shared. The growth performance of Bangladesh needs to be examined from this perspective. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong>South Africa </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The end of apartheid and the coming to power of the African National Congress (ANC) redefined the development paradigm in South Africa. The new government, after many years of social and economic malaise, adopted a neoliberal view on economic development. As a first step, prudent macroeconomic policies combined with political stability had positive effects on investment and GDP growth. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs7.jpg" style="float: right; margin: 0px 0px 0px 10px; width: 325px; height: 195px;" /></div>

<div>

The first democratic government faced the enormous challenge of having South Africa’s development based on cohesion, inclusion and opportunity. The government therefore launched the Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) programme to rectify inequalities by giving economic opportunities to disadvantaged groups. In that sense, it was the first step towards inclusive growth. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

In 1996, the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) strategy followed the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) that was put in place at the end of the apartheid era in 1994. The GEAR strategy focused on (i) macroeconomic stabilization and (ii) trade and financial liberalization as a priority to foster economic growth, increase employment and reduce poverty. The GEAR was designed along the neo-liberal convictions to economic policy where priority was given to liberalize the economy, allow prices, including exchange rates to be determined through market forces, protect property rights, and improve the environment for doing business. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

In 2011, the country joined the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) as an emerging economy with an important regional influence. </div>

<div>

However, South Africa has a long way to go to achieve desired level of inclusive growth. The huge social problems which </div>

<div>

are apartheid’s legacy remain a threat for the socio-political order. In response, the government adopted an ambitious strategy called the New Growth Path that combined the goal of strong economic growth, job creation and broad economic opportunity in one coherent framework. This effort towards greater inclusion is not without challenges. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Recently, official policy has attempted to reorient government spending to fight deprivation in areas such as access to improved health care and quality of education, provision of decent work, sustainability of livelihoods, and development of economic and social infrastructure. </div>

<div>

The South Africa’s government is one of the few in the World which has committed itself to being a developmental state. The definition of a developmental state has increasingly been given to governments that strive to promote social, economic and political inclusiveness by relying on creative interventions where markets fail and complementing them where they thrive through partnerships. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong>India </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

India’s government has made “inclusive growth” a key element of their policy platform, stating as a goal: “Achieving a growth process in which people in different walks in life… feel that they too benefit significantly from the process.” </div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs8.jpg" style="float: left; margin: 0px 10px 0px 0px; width: 255px; height: 315px;" /></div>

<div>

According to the India Economy Review, Economic growth models do not establish or suggest, however, an explicit causal-effect relationship between a country’s rates of economic growth and the resulting poverty reduction, although policymakers often assume an implicit connection. The current literature provides some guidelines about conditions under which economic growth might be ‘inclusive’ or ‘pro-poor’, although how these concepts should be defined remains controversial. One view is that <span style="font-size: 12px;">growth is ‘pro-poor’ only if the incomes of poor people grow faster than those of the population as a whole, i.e., inequality declines. An alternative position is that growth should be considered to be pro-poor as long as poor people also benefit in absolute terms, as reflected in some agreed poverty measure. </span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Asia's third largest economy India has adopted inclusive growth policy in recent years. The Indian government is stressing that the policy is needed in order to reduce poverty and other social and economic disparities, and also to sustain economic growth. In recognition of this, the planning commission of India had made inclusive growth an explicit goal in the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007-2012). The draft of the Twelfth Five Year Plan (2012-2017) lists twelve strategy challenges which continue the focus on inclusive growth. These include enhancing the capacity for growth, generation of employment, development of infrastructure, improved access to quality education, better healthcare, rural transformation, and sustained agricultural growth. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

India’s growth has primarily benefited urban elite and middle class population who are engaged largely in the fast-growing services sector. However, around 70% of the poor are from rural areas where there is a lack of basic social and infrastructure services, such as healthcare, roads, education, and drinking water.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong>Sri Lanka </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The economy of Sri Lanka experienced a rapid growth over the past few years (8.3 percent in year 2011), mainly due to the cessation of the decades long separatist conflict though the year 2012 shows a slight deceleration of growth (to 6.4 percent). </div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs9.jpg" style="float: right; margin: 0px 0px 0px 10px; width: 300px; height: 198px;" /></div>

<div>

However, despite the rapid growth, still there are certain regions, sectors and groups lagging behind. Despite the improvements in growth in all the provinces, the provincial economic contribution pattern has changed only marginally over years. The pattern of growth has remained skewed towards the Western province. Over the years, almost half of the economic activities remained highly concentrated to the Western Province. In year 2012, the contribution of the economic activities of the Western Province was a little over 44 percent of GDP and interestingly, it keeps coming down at present. </div>

<div>

Growth in the overall economy is driven mainly by industry and services sectors. Although growth of the agriculture sector remained low compared to other two sectors, it kept fluctuating highly. For an instance, the growth of the agriculture sector in year 2012 was 5.8 percent, while it was only 1.4 percent in year 2011. The industry sector recorded a steady growth since 2010, from 8.4 to 10.3 percent in 2012. The marked rate of growth of industry sector is led mainly by the growth in construction sub sector. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The contribution of the agricultural sector to the overall economy has kept decreasing over the years and it is at 11.1 percent at present. The contributions of industry and services sectors increased over time, specially the industry sector records a steady increase. At present, the industry and </div>

<div>

services sectors’ contributions are at 31.5 and 57.5 respectively. However, the patterns of sectoral shares were not uniform across provinces and had changed only marginally over the years. The agriculture share of GDP was more pronounced in provinces of Uva, Northern, North-Central and Sabaragamuwa provinces. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Sri Lanka has adopted "Mahinda Chintana" (President Mahinda Rajapaksha's visions for the future) as the inclusive growth policy. It was the presidential election manifesto of Rajapaksha in 2010, but was later adopted as medium-term growth strategy for the country. It envisioned Sri Lanka to be changed as "Wonder of Asia" through inclusive growth acceleration and implementing policies that promote the inclusion of all segments of society in the growth process. After the end of long brutal civil war in 2009, Sri Lanka is witnessing strong economic growth. But, along with it, the rise of inequality is also said to be growing in alarming pace. The Sri Lankan inclusive growth policy includes, increasing investments in various sectors, improving productivity of those investments through innovation policies, skills development and macroeconomic stability.</div>

<div>

<strong> </strong></div>

<div>

<strong>Bhutan </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

‘Gross National Happiness’ (GNH) is the philosophy which forms the cornerstone of Bhutan’s development and which Bhutan is succeeding in implementing. Introduced by the Fourth King of Bhutan in the 1970s, GNH presents an alternative model for development which places equal weight on the social, spiritual, intellectual, cultural and emotional needs of a society as it does on material and economic gain. The GNH philosophy today garners considerable attention as many nations, both developed and developing, assess the merits of development and, in particular, the extent <span style="font-size: 12px;">to which their people’s sense of well-being and happiness is reflected by their levels of material and economic gain. </span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs10.jpg" style="float: left; margin: 0px 10px 0px 0px; width: 300px; height: 272px;" /></div>

<div>

Economic growth moderated to 7.5 per cent in fiscal year 2012 (ended 30 June 2012) from 10.0 per cent a year earlier. The slowdown reflected credit measures taken by the Royal Monetary Authority (RMA) to curb Bhutan's escalating balance of payments deficit with India and alleviate the rupee liquidity crunch. Both general and specific credit restrictions were implemented to constrain imports that are a large component of consumer and investment spending. Reflecting the measures, growth in consumption, which accounts for about three-fifths of gross domestic product (GDP), slowed to 7.8 per cent in FY2012 from 10.0 per cent in FY2011. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Inherent in its Buddhist philosophy and committed to the overarching goals Gross National Happiness – sustainable development, preservation of cultural values, conservation of the environment and good governance - - Bhutan today enjoys a number of development assets, including strong ownership of the development process, low levels of corruption, robust institutions, a well educated and dedicated civil service and visionary leadership. Bhutan is well poised to consolidate and expand on the numerous impressive gains it has achieved since the advent of development planning and its recent smooth transition to democracy. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

According to Asian Development Outlook 2013, growth is expected to recover in FY2013 and reach 8.6 per cent, driven mainly by hydropower and tourism. The contribution of the service sector to growth is expected to improve as the government develops the Bhutan’s tourism potential. As this trend is likely to continue, 8.5 per cent growth is expected in FY2014.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<strong>Brazil </strong></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Countries that pursued inequality-reducing strategies have been warned that growth will be affected, and hence that poverty increases. The harbingers of doom advocated a growth-focused strategy. Their assumption was that the income of the poor rises in direct proportion to economic growth. The truth is more like this: economies with more equal income distribution are likely to achieve higher rates of poverty reduction than very unequal countries. Let’s see if this is the case in Brazil. </div>

<div>

<img alt="" src="/userfiles/images/cs11.jpg" style="float: right; margin: 0px 0px 0px 10px; width: 300px; height: 173px;" /></div>

<div>

Inequality in Brazil, as measured by the Gini coefficient, fell from 0.59 in 2001 to <span style="font-size: 12px;">0.53 in 2007. Much remains unknown about why inequality has fallen, but two sets of known causes stand out. The first consists of improvements in education. In the early and mid 1990s, for example, the workforce gained more equal access to education. This is because of universal admission to primary schooling and lower repetition rates. </span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The impact of improved access to education on primary income distribution was 0.2 Gini points per year from 1995 onwards. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

The second set of factors that reduce inequality are direct cash transfers from the state to families and individuals. These transfers improve secondary income distribution. At the same time, conditional cash transfers, such as Bolsa Família, deliver substantial amounts directly to the poorest families. Together, these changes lead to reductions in inequality of another 0.2 Gini points per year.</div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

A virtuous cycle of increases in the income of poorer families, together with wage growth, has enlarged the domestic market. Greater consumption of mass-market goods has led to growing labour demand for these same families, spurring further increases in their income and purchasing power. For instance, unemployment fell by 22 per cent between 2004 and 2007. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

Brazil still has a high level of inequality and progress in being made towards lowering it. It is too early to say with certainty, but one reason why the financial and economic crisis did not hit Brazil as hard as other countries may be the growing domestic market and changes in the structure of demand created in the last decade. These, in turn were spurred by this virtuous pattern of improved income distribution. </div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

<span style="font-size:11px;"><em>(Source: International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth)</em></span></div>

<div>

</div>

<div>

</div>',

'status' => true,

'publish_date' => '0000-00-00',

'created' => '2013-07-14 00:00:00',

'modified' => '2013-07-14 00:00:00',

'keywords' => 'new business age cover story news & articles, cover story news & articles from new business age nepal, cover story headlines from nepal, current and latest cover story news from nepal, economic news from nepal, nepali cover story economic news and events, ongoing cover story news of nepal',

'description' => 'new business age cover story news & articles, cover story news & articles from new business age nepal, cover story headlines from nepal, current and latest cover story news from nepal, economic news from nepal, nepali cover story economic news and events, ongoing cover story news of nepal',

'sortorder' => '141',

'feature_article' => true,

'user_id' => '0',

'image1' => null,

'image2' => null,

'image3' => null,

'image4' => null

),

'MagazineIssue' => array(

'id' => '279',

'image' => 'small_1372930595.jpg',

'sortorder' => '186',

'published' => true,

'created' => '2013-07-04 02:37:42',

'modified' => null,

'title' => 'Cover Story',

'publish_date' => '2013-07-01',

'parent_id' => '234',

'homepage' => false,

'user_id' => '0'

),

'MagazineCategory' => array(

'id' => null,

'title' => null,

'sortorder' => null,

'status' => null,

'created' => null,

'homepage' => null,

'modified' => null

),

'User' => array(

'password' => '*****',

'id' => null,

'user_detail_id' => null,

'group_id' => null,

'username' => null,

'name' => null,

'email' => null,

'address' => null,

'gender' => null,

'access' => null,

'phone' => null,

'access_type' => null,

'activated' => null,

'sortorder' => null,

'published' => null,

'created' => null,

'last_login' => null,

'ip' => null

),

'MagazineArticleComment' => array(),

'MagazineView' => array(

(int) 0 => array(

'magazine_article_id' => '161',

'hit' => '1572'

)

)

)

$current_user = null

$logged_in = false

$user = null